When is the right time to let your child compete—and how do you keep it fun instead of stressful?

At some point, your child stops just playing sports for fun and starts caring about how they perform. That shift—usually between ages seven and ten—is both exciting and tricky. It’s what coaches call the “golden age” of learning, when kids begin to connect effort, emotion, and confidence through movement.

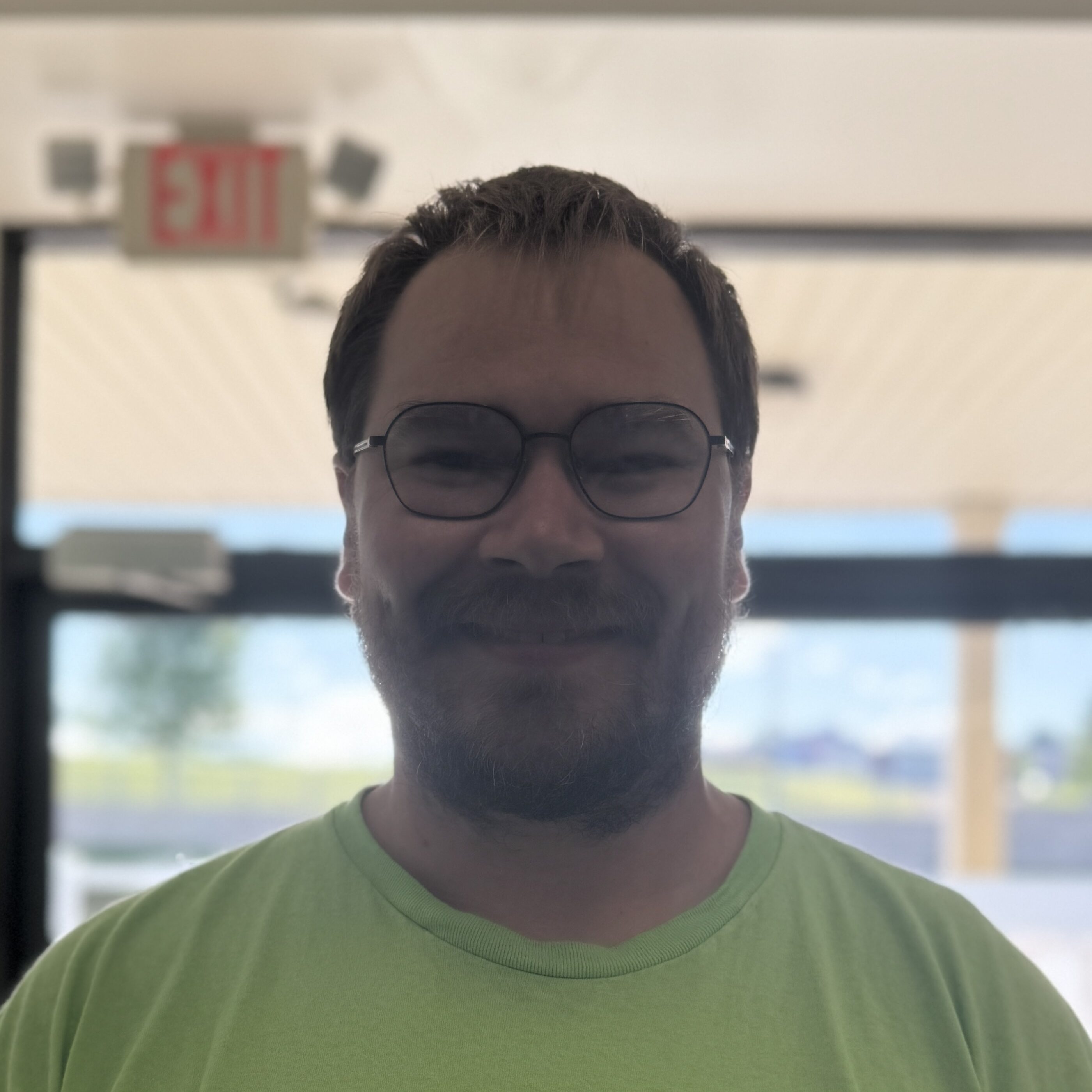

In this episode of Inside the Wave, host Perry Wirth continues his youth sports development series with returning guest Chandler Lewis, Certified Mental Performance Consultant and head coach at Schroeder Swim Team. Together they unpack how to support kids through this stage of growth while keeping sports positive and development-focused.

Catch Up on Part 1 of the Series

If you missed the first episode in this four-part series, start here:

Key Takeaways

In this episode, you’ll learn how to:

- Spot the key PIES shifts (Physical, Intellectual, Emotional, Social) that shape motivation and focus

- Keep practice fun while still introducing structure and accountability

- Help kids manage nerves before competitions with breathing and mindset tools

- Use praise and feedback that build long-term confidence

- Balance play, challenge, and recovery for healthy athletic growth

Standout Quotes

“Between ages seven and ten, kids stop just playing sports and start learning how to compete.”

“Confidence grows when effort is noticed, not just results.”

“The habits built now become the foundation for every skill that follows.”

Where to Listen

🎧 Stream Episode 16 Now:

Connect with Chandler Lewis

- Instagram: @chandlerlewis2323

- Swim Program Contact: [email protected] – official Walter Schroeder Aquatic Center email

- Championship Mind Website: championshipmind.com

About Utopia

At Utopia Martial Arts, we believe sports are more than competition—they’re tools for personal growth. Our programs help kids of all ages build confidence, focus, and resilience both on and off the mats. Inside the Wave extends that mission, bringing real conversations with coaches and experts who share practical ways to help kids thrive in sport and in life.

Why This Episode Matters

The 7–10 age range is a turning point for every young athlete. It’s when skill, focus, and independence start to flourish—and when self-doubt or pressure can appear for the first time.

Chandler’s perspective helps parents and coaches nurture this growth through encouragement, play, and meaningful feedback instead of pressure or comparison. His approach lays the foundation for lifelong confidence and a love for movement that lasts far beyond the early seasons.

Join the Conversation

If you’re raising or coaching a 7–10-year-old, this episode will help you build confident, resilient young athletes who enjoy the process as much as the progress.

Listen now, subscribe, and share this episode with another parent or coach shaping the next generation.

And stay tuned: upcoming episodes in this series will cover ages 7–10, 11–14, and 15–18+, so you’ll have a roadmap for every stage of your child’s athletic journey.

Transcript

PERRY: All right, welcome to the Inside the Wave podcast, where we have super weird conversations before the podcast starts, but I love it every single time. I am here with Chandler Lewis, and we’re on our second episode of our four-part series talking about kids as they grow up through athletic programs and how to approach working with them as parents and coaches, but how to import, import, how to approach competition, which yourself as a swim club owner and a sports psychologist seems to be right in your wheelhouse. Right. So if you didn’t catch our intros earlier, I’m Perry. I’m the owner of Utopia Martial Arts. We’re a martial arts school in Grafton. We have about 200 kids in our program. Chandler, you want to talk about your non-jiu-jitsu club?

CHANDLER: I own and coach at the Schrader Swim Team, and then also I’m a CMPC or Certified Mental Performance Consultant for Championship Mind, which is a consultant business for sports psychology.

PERRY: Let’s talk about Schrader and its kind of claim to fame, right? It’s a pretty big club.

CHANDLER: Yeah. Schrader was built in 1982, I believe.

PERRY: You’ve been running it for that long. Yeah. You don’t look like day over, how old are you, probably 28? I’m 29. That was close, 10 years younger than me. Very close.

CHANDLER: But it was built in 1982 and it was like at that time. It was world-renowned where it was the first 50 meter pool and yeah, especially in this region But there were similar around the country like University, Minnesota took the template of Schrader and built their now awesome big pool and It is held US Nationals juniors collegiate NCAA championships, there’s been world records set at the pool and Yeah. And it’s been a kind of a staple in the swimming community. I get any time I go throughout the country, like Schrader. Oh, I swam there. It’s like a very staple in our community.

PERRY: I remember even growing up, like when I was doing, we were talking about on the last episode, how we both did swim lessons at Cedarburg pool. But I remember the kids at Cedarburg pool being like, Oh, I go to Schrader. It is that prestigious. You do everything from five-year-olds to Olympic hopefuls. What age do you guys typically stop?

CHANDLER: Honestly, we have a sweet we have our competition program where like we’ll have post grads Currently right now and this is interesting is we have a college athlete That swam at University, Wisconsin. It was the fast going into college. He was the fastest recruit in the hunter backstroke in his class He made the Pan American team. Sir.

PERRY: Mac won all thanks to your coaching. I

CHANDLER: a combination of a lot of efforts, but he goes to Wisconsin, he does well, but not at the level that we all knew that he could. He ended up, they got a new coach, he ended up transferring, going through the transfer portal, and he settled on Seminole University, Wisconsin, Milwaukee. However, he’s gonna train with us, which is a very not normal thing. He already will have school records. He will go to NCAA championships. So for the school standpoint, really big opportunity. but he feels connected to the Schrader program being his best place to train, which I think just shows what we provide for athletes. Not saying that we’re the best coaches, but I think that we provide a lot for high school and post-graduates, uh, eventually the goal, and it has always been the goal is being able to host and have postgraduate athletes that are competing for Olympics. And there could be a hub in this area for professional types.

PERRY: It’s such a cool mission. You guys are on. Um, and I know we’re not talking about, uh, that age group today, like the high school and beyond, which is going to be a really fun podcast. I’m excited for that one. But today we’re talking about seven to 10 year olds, right? Uh, that like golden age of motor learning skills, like such cool stuff starts happening with competition in that age group. You know, myself watching jiu-jitsu, it’s like, that’s where kids jiu-jitsu starts looking good. Right? Like they started looking like little athletes at that age. Um, five and six was fun. right? That was our last podcast. It’s like getting their toes wet in competition, getting them used to sport. But seven to 10. That’s where a lot of like magic happens. So we’re gonna follow the same format that we did last time where we start talking about the developmental stages of the kids these age, right pies, the athletic development, and then how those two end up being the building blocks to approaching competition. how to approach competition, and a lot of practical tips for parents and coaches to take home if you’re a parent of kids these ages, 7 to 10, or if you’re a coach for kids ages 7 to 10. So let’s talk ages of development. And I break this down smaller because this is kind of what we do at our academy, but I did 7 to 8 year olds and 9 to 10. Even though we’re clumping these together from a competition standpoint, physically, intellectually, emotionally and socially, that’s our pies. There’s a huge difference between a seven year old and a 10 year old. And we need to remember, these are all based on like a curve, right? Some kids might be very well physically above the curve, right above average, and they might be behind emotionally. And understanding these building blocks is important because you as a coach, coaching that athlete is going to be much different. And we might need to focus on different things and different strategies, right? If we’re able to work with a kid who’s 7, but we identify that physically they’re 9, maybe intellectually they’re 9, but emotionally and socially they’re still 7, or maybe even 6, it’s totally different. So let’s talk about physical, 7 and 8-year-olds. weak, fine motor control. They still stumble and it’s very dynamic moves. Their technique can be shaky, but typically only gets shaky when they start pushing it. Right. So in controlled environments, they do really well. But when they’re trying to go fast, their technique starts failing. I’m going to use the golf analogy, right? When I learned how to golf, just crush the ball. Swing that club as fast as possible. All your technique goes away. And that’s probably the age I was golfing at. So that’s a big thing that we need to focus on for 7 and 8. 9 to 10, that technique starts getting even more solid. The agility gets solid. The problem is sometimes you start getting lazy. So they’re good. They’re just not trying that hard.

CHANDLER: Cause they’re like, well, why should I?

PERRY: Right. And that does lead to sloppy basics. What do you see in the pool? Um, and your athletic trainer, you guys do pool and, you know, land training as well, but like. physically from kids these ages, like what are you seeing?

CHANDLER: Yeah, I mean, there’s obviously a big difference between seven and 10 year olds, but seven to eight year olds, I feel are starting to understand the sport differently, like mechanically. Yeah. Like you can start talking to a seven to eight year old, technically, a little bit more.

PERRY: Yeah, it’s like, it’s not just about like, Who’s trying harder. Right. When you’re younger, sometimes it’s just like who tries harder and goes like literally moves their body. The fastest is going to win, but they could start realizing like technique matters.

CHANDLER: Yeah. And they have a greater understanding of technique. You know, by the time, I believe that if the kid was on some team in five and six and now they’re progressing to seven, eight, they’ve obviously for us, they’ve switched groups. So they went from the pre some team or the introduction to some team into, okay, now you’re in a, we call it trader stars or superstars or, um, uh, That’s a progression in groups. So they’re in the water longer. Practice is longer.

PERRY: Well, because they’re strong, like they’re strong enough for it, right? Like little kids, they just don’t have enough caloric expenditure and strength to be at practice that long. And when you’re not at practice that long and you don’t have that attention span, you can’t develop as much technique. Right. Um, so that’s freeing to you as a coach. Yeah. Awesome. What else are you seeing?

CHANDLER: Well, I think for us, it’s like that now begins the formalization of practice. Like now we’re getting into some practice that’s every day, this is what we do. We start off like this and then we go into our warmup and then we’re gonna work on these skills and maybe today is this type of day. It’s like practice isn’t as random or there’s a little bit more time spent on the formalization of like, not training, but practice.

PERRY: It’s more, it’s a little bit more disciplined.

CHANDLER: Yes. More disciplined. They’re introducing bigger skills, harder skills, technical skills. And then, you know, like kids are racing more often, so we need to have an understanding of racing and how that works. And, um, at five and six, you’re just trying to introduce those. They’re intellectually, they’re, they’re completely different.

PERRY: Yeah, which brings us to intellectual, right? Seven and eight, very smart. They are sponges. They are sponges that are easily distracted. Yep. Right? For sure. They can often overthink, and sometimes they forget the simplest of things, which is challenging. Yeah. Right? Nine to 10, they finally start developing some critical thinking. Uh, their decision-making isn’t the fastest, right? They can make decisions, but it takes a while to do it. Um, I don’t know if that shows up in the pool. Definitely shows up in jiu-jitsu match. Like if you’re slow at making a decision, the other person just took you down. Um, And the other intellectual challenge for 9 to 10 is they’ll start prioritizing effort. They’ll pick the easy way sometimes, not the way that’s going to require more effort. And when you’re in practice and you try to cheat at doing the easy way, you don’t develop the way that you should. How does that show up in the pool for you?

CHANDLER: Uh, I think the big intellectual change for us, especially from five to six, seven and eight, it’s like, obviously you’re introducing the technical and tactical things within race strategy, but seven to eight to nine and 10, nine and 10 year olds will be able to formulate a race plan, execute a race plan, and then review that race plan after the race.

PERRY: Let’s talk about, because I don’t even know. I mean, I can guess what a race plan is, but like, what is an example of a race plan?

CHANDLER: So like, for example, let’s say I’m swimming a hundred backstroke, a race plan could be something like, I’m going to get out fast and relax. I’m going to try to make a move on the third 25. And then I’m going to maintain four dolphin kicks off each wall. That’s a very basic race plan. And a nine and 10 year old can spit that out. Yeah. they can formulate that on their own. They will need some support, like, hey, what’s our race plan? I’m not really sure, and then you can spit it back, and they’ll accept it, and they’ll try and execute it, and then afterwards, they will be able to come back and say, I didn’t go out fast enough, I need to make sure that I go attack the first 25 better. 9 and 10-year-olds can do that. 7 and 8-year-olds are not there yet. They might say something like, it didn’t feel fast or whatever, but 9 and 10 is a big learning group.

PERRY: Same thing for us. 7 and 8, they know a bunch of techniques. They don’t know how to necessarily assemble them.

CHANDLER: Yeah, and like the reviewing the post race review. Yeah, with a nine 10 year old is going to be completely different between a seven year old seven eight year olds like nice job high five. Yeah, walk away nine and 10 year old. There might be some emotion mixed in it now. And now you got to walk. Well, why didn’t that work? Well, well, let’s talk through it. There’s going to be some, like the communication piece is much bigger. And I think that’s a big change. And similarly with practice too, nine and 10 year olds are starting to quote unquote train. In our program, we value technically, but there’s coaches out there in the swimming world where they believe now’s the time to throw in the aerobic base and develop the aerobic base before puberty. My experience as an athlete, at 10 years old, I was swimming five to six times a week for an hour and a half, and training. Yeah. We try to limit that. There is some exposure to like, we’re going to do some repeats. We’re going to stay on intervals. Yep. Like you can start developing that at nine, 10 at eight, we’re not doing intervals.

PERRY: All right. Is there, so when a kid goes to a swim meet and just general question, from my knowledge, do they know how many races they’re going to have to do? Yeah. Okay. So it’s kind of predictable on how much the challenge in jiu-jitsu is like when you go to a tournament, if you’re in a division with three or you’re in division with 10, you don’t know what your base needs to be.

CHANDLER: Right.

PERRY: Yeah. Um, you also don’t know because. Matches are a variable amount of time, you know, maybe for that age group, like three minutes. But if you win right away, you don’t have to do all three minutes. So if you have five minutes, but all five matches go the distance, like your aerobic pace needs to be a lot better. right, so like you you probably really only need to get them to Like minimal viable aerobic base.

CHANDLER: Yeah, and I think the idea of training a nine and ten-year-old I They don’t have to be workhorses. There’s no way that you’re like, oh, we’re developing speed for this ten-year-old but there’s coaches that think that way and I parents 150% where it’s like this idea of developing bases and speed and they need to train more. But that’s a big change is like the seven, eight year old group. We are not training. We’re not, maybe there’s some intervals, but like at the nine, 10 group, they’re going to get introduced into intervals and like, we’re going to mix it up with different type of volumes and yeah. Um, it’s definitely an increase in like the intellectual side of like knowing how practice and training works.

PERRY: We, you know, it’s more on the physical side, but like that is the age where at least in my competition class, because we have we have two classes for kids at art academy, right? We have our explorers program, which is really for someone to truly explore Brazilian jiu jitsu, learn the self defense side of it. But then we have a competition side where we take the the martial art and do the sport side of the martial art. And in my advanced Competition class like that’s when we’ll start doing some like workouts at that age But they’re all like competitive fun workouts that the kids like it’s not like hey, we’re not just gonna roll run wind sprints Right try to hide them at least a little bit Yeah through games like relay races and stuff like that. Like there’s other ways to build that aerobic base. That’s not just a laps.

CHANDLER: Yeah, definitely not. And I don’t think that’s the correct way of long term.

PERRY: And if you do that, it brings us to the next one. It’s like the emotional stages of development. Again, much different between these two age groups. Seven and eight year olds, you know, compared to the younger ages, they’re a lot more emotionally stable. They are starting to learn how to communicate their emotions, but they also, because of where they’re at socially, they’ll sometimes develop big emotions when they’re put on the spot. Um, nine to 10, a lot of their motivation that we need to work around is like just motivational swings, like high motivation, low motivation, and they’re very motivated by their peers and what their peers think. Um, What do you notice as a sports psychologist? Cause this is kind of like your sweet spot, right?

CHANDLER: This is when the, I think this is when. Emotions start playing into especially competition. Yeah. Like it could be a huge, like that’s, that’s why you win or lose, right? You will, you can go to any summit throughout the country. Doesn’t matter what the level is. If you go to a nine and 10, even 78 year old swimming, you will see crying. Oh yeah. Big time. Yeah. Like you will see enormous amount of crying.

PERRY: And is it just when kids lose, or is it like the pre-competition jitter cries too?

CHANDLER: I think it’s a combination of things. Obviously, there’s kids that are nervous to compete. That’s definitely a thing. Normally though, the crying, especially at 9 and 10, are going to be, I wanted to go at best time, I didn’t go at best time. Or I wanted to beat this person, I want to get this result, and I didn’t get it. And it’s like the first, I think it’s the first initial stages into like competing at a higher level. It’s not high. Like we’ll look at it and be like, that’s not higher level, but it is for them. It’s a jump. Now they’re going, they might go to state competitions. They might be racing kids within the state of Wisconsin that are outside of our region. There’s definitely like we have introductions to, uh, we call them zone competitions, which is like, all right, we’re going to go compete against Michigan, Illinois, you know? And so it’s like that introduction starts at nine and 10, which can lead into pressure, expectation, anxiety, which leads to the crying, the frustration. Um, And that’s probably parental forced, but it is a thing where it’s like, kids wanna go fast and get better. And when they don’t see their time dropping, they think it’s a direct correlation into who they are. And as a coach at this time, you play a big factor in how they regulate their emotions.

PERRY: And the big thing is parents out there like, you need to realize that this is like we go into it knowing that this is a thing yep like it’s expected so parents of you know kids these ages if your kid is crying because they lost as expected yeah right the the kids that are in the higher percentile here they’ve already learned how to deal with those and to leverage them. And nothing that we’re saying is like good or bad on all these, they’re just facts, right? And I think that’s why we’re doing this podcast is so parents know like what is expected and how do we help develop that kid to be even better, right? We want every kid to be above the curve. Right? We don’t want just the average B students. We want to take all those B students and try to make them A students in every single subject. And we also need to realize that every kid is gonna be different in different areas. You might have a under physical developed child who’s incredibly bright. Very great technique because they’ve learned it intellectually, but they don’t have the stamina or physical development to do a long distance of it. You might have a kid that’s really smart, really intellectual, not good at competition because they’re emotional is behind, right? And these are just all things. Nothing’s good, nothing’s bad. These end up just like winning and losing in competition, both can be a superpower if you use it right. It’s funny, this month at our academy, we talk about a different word of the month every month and it’s humility, which we define as the kids is the superpower in understanding your strengths and your weaknesses. That’s good. It’s so important. And that’s my message to the parents here. It’s like, you just need to know where your kid’s at. Nothing’s good, nothing’s bad. It is what it is and we just wanna make it better. Social side. Man, these ages. They love interaction. very loud if they even think something may be unfair. Their peers drive their effort. You know, this is a time where kids might start switching sports because it’s a sports that their friends do. I’m sure this might be a sport because swimming and jiu-jitsu is interesting because it’s not in the school with all of their 25 peers in their homeroom class, right? So quite often, we get kids that go to other sports because they want that peer approval of like, oh, that’s what my other friends in school do. But again, it’s a superpower as a team, right? If you get your team all rowing the boat in the same direction, that peer approval is even better. The other challenge socially is the kids might hold back if they’re feeling socially uncomfortable. Right. Um, what do you see socially? A lot on your team, because you have a, you have a big team and you have a very diverse team as well.

CHANDLER: A lot of comparison for sure. Like that this at nine and 10 kids are comparing each other, but they do. I think that they naturally want to work with each other. They naturally, I think this is a great time where you develop like that teammate type of mentality. Yeah. Um, because they naturally are gravitating towards each other. Yeah. Uh, like they can start recognizing, Oh, like I’m bigger. This is a bigger ecosystem than just me. It’s my team. And, uh, we do a lot of like introduction to cheers. Yeah.

PERRY: Yeah. So, uh, you know, swimming individual sport primarily, right. There’s a team aspect to it, but how do you guys develop kids socially being in reality, an individual sport?

CHANDLER: Yeah, I mean, they have to work together on relays. We have a thing called the Schrader Way, which is team first, act with integrity, expect success, which is really, it’s called the Schrader Way. And at this nine and 10 age is the time where we really, we’re developing that, but we try to get the kids to do that on their own where they’re setting the standard with each other. And part of that is like when you’re on a relay like you’re working as a group for a combined effort Yeah, you know we talked about a lot when we put a team banner like national champions. We never put like a you know, like X natural champion, it’s Schrader. It’s like that combined effort. And more recently we’ve been trying to do, I call it Initiative X, which is the idea that trying to get the young kids bought into the idea that you are helping these older kids go to national competitions and you are part of this Schrader team. And at this nine and 10 age, you can start really kind of like putting in that social awareness of like, you are part of this team. That means that you act this specific way. We’re setting the standard of being great, acting with integrity, expect success, team first. What does that mean in practice? And you know, I think at that 9-10 age, you can really set those values and standards.

PERRY: Man, I totally agree. They’re just socially developed to this point where teamwork and culture matters to them. Even in school, they start getting their little clicks and stuff like that. But in reality, these pies and stages of development, they’re the foundation of everything that we do. We need to understand as coaches, as parents, where our kids are at. And every athlete is at their own spot. And it’s the spot that’s perfect for them, us as coaches, is to push them and get them ready for that next level. and hopefully bring up their average as we go. But this is the building blocks for athletic development. And I think at these ages, you can start working on it more. They’re not necessarily hitting the weight room yet. They’re not doing a lot of like cross training or supplemental training, but we can still do a lot outside of just teaching them how to swim or teaching them how to do a rear naked choke. What’s your approach of just sheer athletic development?

CHANDLER: Yeah.

PERRY: For these ages.

CHANDLER: I mean, at this point, we’re trying to teach land athletes to be water athletes. You know, like you have to learn on land before you go into water. I think that most coaches in the swimming community think about water specifically. Yeah. And they don’t think about land. I think more on the side of building land athletes that are also water athletes. Like you got to think you’re in a different ecosystem. Yeah. But that doesn’t mean that you can’t build athleticism on land. So like learning how to jump seems easy to teach. And then he also seems like, well, you just jump. Yeah. But that is a hard skill to really perfect.

PERRY: I mean, especially when you’re talking about jumping in a race, there’s reaction time, right? Right. So it’s not just like, how, I’m gonna say how hard you can jump, high, far, whatever it might be, but you need to jump at the right time.

CHANDLER: But it’s like, that development can be done on land. For sure. And probably much higher repetition. And awareness is bigger at this age. Thinking back to when I was a string coach, We were coaching kids at nine and 10. We were not coaching kids at seven and eight. Like we’re coaching kids now. We’re teaching kids how to properly move.

PERRY: This is that age that I think you can start doing like really high level, like detail level, like agility drills and coordination stuff, like ladder drills and jumping rope, which is all like, fun stuff for kids to do that is going to be way more fun than bench press, which they should be doing at this age anyways.

CHANDLER: Yeah. It’s like trying to trick them to learn athletic development.

PERRY: Yeah, for sure. But how about as they get older, like verging on 10 years old, where you can really start developing body weight strength exercises, like push-ups, squats, wall sits. Push-ups, squats.

CHANDLER: Lunges, walking lunges.

PERRY: The kids at my gym. Have you ever seen the Sally Goes Up, Sally Goes Down workout where he’d squat? They love that. And I’m like, why do you love this so much? It’s literally five minutes of hundreds of squats. Or a deck of cards. They love doing deck of cards. It doesn’t matter what the exercise is. As long as they get to pick their fate, they’re OK with it. I’ll do other stuff like make them hold a plank. This is one of their favorite ones. They have to hold a plank, like a hand plank, and I ask them random trivia questions. So like, ChadGBT, give me 20 trivia questions in, whatever, various school categories for 10-year-olds that I can ask them. And as they’re doing a plank, I ask them the trivia questions. If they get them wrong, they have to do like three push-ups. but they love it. It’s a great age that they can start developing some strength, but body weight. What else are you guys doing on land as they start getting towards that 10?

CHANDLER: I feel like this is the time where you can teach hinging, which is hard. You know, one of the things that I think that we do at 10 years old, that the nine and 10 group that is different than seven, eight is, uh, you know, our younger kid coach or age group coach starts doing this thing called whiteboard Wednesdays, which is really good. Uh, but you gotta be like, you cannot be eight years old and send this and sit still. Cause it’s going to be 15 minutes. And we’re going to talk about something that could be a goal type, like we’re going to talk about long-term goals or specific process goals. Or like today, we’re going to talk about what it means like to be a good teammate. Those are like, I think are also LAN things that we do that translate into like, when you’re a nine and 10, we’re going whiteboard Wednesdays. What does that mean? Well, you’re going to have to write on the note card. three specific process goals for this month, right? At seven and eight, they’re not doing that. That’s hard.

PERRY: Do you start, like when they are nine and 10, do you start doing like speed development? Because I know you don’t do that too young, but I think like nine and 10, they can actually start working on Developing. Yeah, like some explosiveness. Yeah, definitely. Definitely. Awesome. Any other big athletic development things for these age groups? I think they’re like, they’re just getting started. I think we get a lot of parents that want to push the athletic development too far at this age.

CHANDLER: That’s the issue that I think that we that we run into is that their parents are more eager to want more and want more and want more. And you’re trying to think about long term what’s the best for the progression. Because we want them to have more when they turn 11 and 12 and then 13, 14. And it’s a mistake if you’re pushed too early on.

PERRY: And there’s still, you know, we’re going to get into competition next. And there’s still like really just truly getting into competition at this age. So you still need to keep it sort of fun. If you take away all that fun and you do just like laps or wind sprints or whatever it might be, like you’re going to lose the kids right away.

CHANDLER: Like training. Yeah. If you’re training at nine and 10. Yeah. That’s not, that’s not the goal. Yeah. You’re learning. You’re having fun. You’re, you’re doing this for enjoyment. Yeah. Not for like, it’s still training apps. Super social. Yes. Has to be.

PERRY: Yeah. Man, let’s talk about competition, because this is where we typically spend most of our time on these. Seven and eight-year-olds, they can start following more rules, more structure to competition. They get distracted, but they’re better at getting their focus back. Um, and some of them want to like actually test their skills and they want to go out there on their own to do it. I think the ages before the parents and the coaches are like, Hey, let’s get you out there. They’re encouraged. But at this age, you start getting like, I want to compete. Um, do you see the same thing?

CHANDLER: Yes, definitely. And there’s definitely a clear difference though, between seven and eight and nine and 10 for sure. Like, you know, like seven, seven, eight year olds are going to get exposed a little bit more to competition. Now, instead of doing our in-house competition, now they’re doing their first meets where they’re racing against kids on other teams. That’s a big, that’s a big jump. Sure. Huge. Because it’s like, oh, I’m not racing my buddies. I’m racing this other team.

PERRY: Well, here’s the thing, right? Part of ecological learning or learning through a game structure is environmental changes, right? And our in-house is the way it is because everyone there, the kids typically know, the kids know the kid’s there, the kid’s parents are there, right? There’s not really a true stranger in the room. It’s in a place that’s familiar to them. It’s on the same mats, right? It’s the same routine where the kids wash their feet before they get on the mat. it’s the referees are people they see around the academy. The second you take that competition, and you put it in a different spot, yep. The fact that the pool is different, maybe the walls are a different color, there’s different noises, there’s a different location, there’s the locker room is different, right? People don’t realize that, even though it’s like you’re going from like, just the competition side of things to a new environment with new people is a huge jump. It’s hard to describe how big it is. And it’s important as coaches and parents to make sure that the kids still have a good experience with that.

CHANDLER: Totally. For us too, it’s the, if you’re going from, if you’re in some team at five and six, even seven, and we have kids that stay in our pre-sum team to like eight years old. When they’re doing the in-house competitions, the referees there are just trying to help them. When they progress into USA Swimming competitions, now they’re gonna get introduced to, ooh, I got disqualified. That is big. So that’s when the crying and emotions.

PERRY: I I mean even at our in-house like our referees like we have we have two coaches Or one coach at every mat and the coach coaches both kids, right, you know in a regular tournament Like I’m not coaching another gyms student, but the referee will sit there and like talk with the kids a tournament that ref is quiet

CHANDLER: Yep. They’re going to do their job.

PERRY: Throwing up points. They’re giving out penalties. It’s just so different.

CHANDLER: It’s a big change. And that seven and eight group, if you progress into that, where now you’re doing USA swimming competitions, and it might be nine for some kids. But that’s the big jump. And then similarly with our older kids, the big jump is now it’s, you know, the rankings and times and standards where they know exactly, okay, what is 30 seconds in the 50 free mean at my age? Well, that means I’m a triple A swimmer or quadruple A swimmer. That means I make the zone meet. That means I make the state meet. That means I’m at regionals. Yeah, interesting. They start really identifying what level of athlete they are. And so that’s why the competition has to have values around it with coaches and also as parents. That becomes number one, in my opinion.

PERRY: Yeah. Man, and even as they get older, they… start understanding, at least in jiu-jitsu, they start understanding the scoring better and like why they won and why they lost. And which adds a whole nother dynamic to it because sometimes at seven and eight, like the kids don’t necessarily know why they won. Um, in jiu-jitsu, like if you win by submission, they’ll typically know like, Oh, I tapped that other person out. Right. But if there’s points at the end, they’re like, Oh, how did I, how did I have more points than them? But as they get to that 10-year-old age, they actually understand the point structure of Jiu-Jitsu and how points are scored and things like that, which changes the game in Jiu-Jitsu because you can play the game of points.

CHANDLER: I’ll say it like this, and I don’t think this is unnormal. I remember how fast I went when I was 10. Really? I know my times. Why, why 10? And that’s, that’s when I start recognizing, I know my, I do not remember my times at nine. I have no clue how fast I went at eight, but I know exactly how fast I went at specific competitions starting at the age of 10. And I think if you were to survey most Athletes that went through their career from 10 to 20 competitors. Yeah, this is when that age 9 and 10 they start identifying Results like very clearly and they know I made zones when I was 10 I made I got this place when I was 10 I went this time when I was 10 and So it’s, and that’s not unnormal for our sport perspective, is that this is the age, I think naturally through this, how competition is set up, where we’re going to start ranking kids. And we know who the best kid in the state is in this event is. And it’s probably a coaching thing too. where we play, okay, well, you know, Bobby’s getting a little bit more attention to practice. He might be a little bit better than me. And then parents. That’s when it, you’re, the development of, and I talked about this in my thesis a lot, is like the development of sports specific values. really comes into play at nine and 10, where it’s like you are developing these long term sports specific values, for example, a sport specific value that I never got over that I should have gone over that was developed by a coach, for sure, at the age of 10 was counting every yard that I swam. And I started that at 10. So I would count up how much volume do we do today at 10? We did 4000 yards at 22 years old, I was counting every lap. Is it then that’s a bad thing to do? I think it’s a The bad thing was is that I resulted volume in compared to how much I’m getting done. We did 6,000 yards, that was good practice. Which in the sport of swimming, there’s a very big sport specific value over amount of volume. And that was developed for me at 10 years old. And other kids get those type of values. So it’s best times meet a good race. you can set sports specific values early on at that at executional, controllable things. Yeah, as a coach, as a parent. And as an athlete, where it’s like, how, how am I grading myself on performance? Well, I’m grading myself on how I will I execute my controllables? How well I prepared? How will I control my emotions before race?

PERRY: Let’s talk about those. So the controlling the controllables, because they can seven to 10, they can actually start doing this. What are those controllables? Sports agnostic. We’ll use swimming and martial arts as an example.

CHANDLER: One of the things that we do that I think at this age group is different and you should start doing is the introduction to some mental tools, mental performance tools. One of them, what I call is the battle behind the blocks. It’s like you’re about to race. You’re behind the block. There’s gonna be a battle that you’re trying to win, an internal battle. And then there’s gonna be a battle in the water, when you dive in the water. But we talk about the idea of power posing, utilizing your breath. That’s a controllable thing. Visualize that race execution. What do you wanna do? What are you trying to accomplish? What’s your race plan?

PERRY: What are those controllables? One of the best clips that we had from the first podcast that we did with each other was the stoplights, the green-yellow. Let’s talk about that one really quick. That’s a really great tool for this age group, I think.

CHANDLER: Yeah, nine and 10, it’s like you can start identifying those really basic green light, yellow light, red light type of routines, or also like recognitions. It’s like green light, I’m in the zone. Ready to rock. I’m ready to go. I’m behind that block. I got my Superman pose, and I’m like, I’m the hunter. Here we go. You’re in green light. Yellow light’s the kid that’s behind the block that’s making himself a little bit smaller. They’re thinking about the guy next to me. He’s so much faster than me. He’s not controlling that battle behind the block. Red light is a kid that’s probably crying behind the block at this age. You can get kids to identify where they’re at, but we have kids at 9 and 10. Well, We’ll talk about, hey, this is a good routine behind the block. This is a good routine or script that we have within the water. We want to get out fast. We want to make a move. We want to finish in hunt and kill. That’s a very basic race execution. We teach that. And then we also teach the battle behind the block of Superman pose, utilize the breath, focus on your execution. And then the kids will come back after race and they’ll talk about that. So we’ll say something like, how well do you execute your race? Or with a 9-10 year old, you might be like, What do you think about your race execution? And they might say, you know, I need to do this better and this better. Okay, what about your battle behind the blocks? How was that? And they’ll be able to spit it back.

PERRY: Oh, man. So at this age, you’re actually able to get them to reflect on almost all parts of their performance, like the before, the during, and the after.

CHANDLER: And them taking control. Yeah, that’s awesome. The problem that we run into is coaches are speaking this language, and parents are speaking this other language. Yeah. And that’s where the confusion comes into place.

PERRY: What suggestions do you have for parents as their kids are competing in this age, like the do’s and don’ts?

CHANDLER: Well, I think at this age, especially 9 and 10, you have to be aware that your kid knows, they will know, whether they succeeded their goal or not. They know what’s good, what is not. You do not need to tell them. Oh, you didn’t go a best time. Oh, you didn’t win. You could have done this differently. You do not need to be coaching them, like at all. If you’re coaching them through sports specific tools, I think that you’re going to go down a path that is going to lead to destruction. If you’re coaching your kid in that car ride, you could have done this better. Why didn’t you do this? What do you think about that? This is when this really comes into play, and it’s so recognizable with the kids that we see. The kids that are so strung out before a race, we know that parent is in their ear.

PERRY: What are some things that parents like, just man, sometimes they just need a one-liner that they can repeat like a parent, right? Like what are some one-liners before the race that a parent can say to the kid that’s gonna have a positive impact?

CHANDLER: So I did an activity with my older kids, but it translates to younger kids. I had, and it was really, really for the parents, but I tricked them. So I had them write out three different no cards. Before I race, I need from my coaches, and they wrote down three things. Before I race from my parents, this is what I need. Before I race from my teammates, this is what I need. And then it was after I race, this is what I need. After I race, this is what I need. Really what I was trying to do was get that parent no code, and then I was gonna share it to the team. One of the very clear, identifiable things that was recognized by almost every athlete was before I race, do not talk to me about my race. Don’t say anything. Don’t say anything. Don’t try to coach me. Let me have some freedom. Yeah, right you give your kid freedom to just like go out there and have some fun. Yeah, great 10 out of 10 and then after they race One of the things that the kid said that was like I need you and I these were 15 8 year old kids Get me a good meal. That was it. That was on every single card. I don’t need you to walk me through my race. I don’t need you to tell me what I need to do better. I don’t need you to talk to my coach. All I need you to do is tell me good job and get me a meal. It is that simple. One of the things that I’ve been doing that I shared to our parents, which is really good, is kids would finish a race and I would say something like, what are you proud of? And it, first of all, it puts the proud ownership in me. But also as a parent, that’s also, you can say that to your kid. Hey, I’m really proud of you. Or hey, what are you proud of? You did really well. That’s great.

PERRY: And we actually pivot, we try to have parents pivot saying, hey, I’m proud of you, to say, you should be proud of yourself. Because most kids, they know their parents are proud of them. But what you want your kid to develop is pride within themselves.

null: 100%.

CHANDLER: Proud that what they did was good. Ownership. Take pride of what you’re doing. So that question of, what are you proud of, is the first question that I ask. One of the greatest things a parent can say, I think, in our sport is, I love to watch you compete. That is game changer. I love to watch you compete. You just go out there and you just let it rip. I love watching you compete. When someone hears that, it’s like, you’re not talking about how great they are. You’re just like, I love watching you race. It’s so cool watching you put it on the line out there. That’s a great line that a parent could use that doesn’t put pressure into performance on outcomes, results. At this age, if you can stay as far as you can away from times, outcomes, social comparisons identification of how good you are. Yeah. Oh, you do you want to swim in cow? No, absolutely not. You know, and this is when it starts.

PERRY: Yeah, man. I feel like at this age, you get some of those parents, man, probably even younger, just because it’s parents, right? Where it’s like, I got your 10 year old, they’re gonna go swim at, they’re gonna go swim in Minnesota or Madison, or like whatever, XYZ is the best swimming school ever. And kids have challenges with that pressure. Almost like anti, like, oh, you want me to go swim in college? I’m gonna just not swim anymore. How do you coach parents around that? Because you can’t just be like, stop.

CHANDLER: Yeah, you can’t. And the other thing, too, is what we’ve led into is you can try your absolute best on coaching parents. You can teach them all the things. You can send out surveys. You can send out newsletters like, hey, this is,

PERRY: scientific study proven that if you talk like this, it’s hard because people just get in patterns and you know, they’re, they’re coaching from their parents, from their last experience in athletics, not their experience when they were 10 years old in athletics. Right. Right. Like they’re coaching those parents that are the parents that typically look, in my opinion, look at their kids to become college athletes in a sport. When they’re 10 years old, we’re also college athletes in that sport. Like they want their kid to do what they did. or they want their kid to get to the level in some sport that they did. And it’s so challenging. Parents, you need to not look at it like you’re a senior in college in your last year and this is it. They’re 10, many years ahead to even get them there.

CHANDLER: Yeah, and I you know, we have we have two different type of parents in this group Some of our best parents. Yeah are the ones that? Succeeded at the highest levels. Yep, like some of our best ones are those people. Because they’re like, I know what’s coming down the road. I know that this is going to get really hard. And this is my experience at 10, and if I would have gone through it again, I would have done it differently. We have those parents, and they’re the absolute best. So hands-off. They let the coaches coach. They let their kids fail. It’s 10 out of 10 great. We also have the flip side. of parents that succeeded at a high level, that are gripping their kids as hard as they can, because they definitely think about their experience and thought, this is how it’s done, and this is how I was coached, or differently, I think I should have gone coached like this. I do think that we also have another group of parents that don’t know right from wrong at all, right? So you have this impact that early on where you can set the standard of what we expect from parents. Like we talked about last time, you have a parent handbook. We have a parent handbook. You have to have that.

PERRY: We even at our, and we made a point of this, when we do our in-house tournament, Jeremo’s there, he films it all the time, every time we do when he comes out. Before we start the tournament, we do a talk to the parents. We say, hey parents, here’s what we expect from you. Here’s what your kids need from you. So we use that tournament, we have all the parents there, and I explain the rules, I explain the scoring, I walk through the format, I tell the kids where they’re gonna be, then we get the parents to listen. Like, hey, this is what expected to you. Cheer for the other kid, give them positive vibes, say all those things that we just talked about and then like, that’s it. Leave the coaching to the coaches. If your kid’s crying on the side, we will take care of it.

CHANDLER: Yeah. And it’s, it’s like, when I first started coaching, I would get very angry with like these parents that were interjecting. I started more recently looking at it, like every parent wants their kid to succeed. For sure.

PERRY: They want their kid to be, they want their kid to be the best. They want their kid to have fun.

CHANDLER: And everyone wants that. And it, you know, this manipulative kind of grip holding behavior, though, it’s very bad. It is coming from a place where they deeply care. And if you can get As a coach, you can flip that and say, all right, this parent cares. I have to express to them that we also really care. And we’re just doing it a little bit differently. So when we don’t go over to Johnny when he’s crying because he lost, that doesn’t mean that we don’t care. We know that he needs to go through that to learn X so that when he’s 13, 14 years old and there’s pressure and expectation on the line, He can handle that, and that’s how we’re showing that we’re caring. When you interject that, you lose this and that. I think I’ve switched that mentality, and it’s been more helpful for me when communicating with parents.

PERRY: Yeah. What are some other good tools that we can use on this age group? We talked about the stoplight is a good one. I like, I love the power post one. That one is, you know, amazing. I think, you know, visualization can be good at this age. Not necessarily like visualizing, uh, yourself winning, but visualizing the past, right? Like having the kids start thinking about. anchoring moments that they’ve had in the past, like tell me about a time that you were really confident or really proud of yourself. Cool. Think about that before your race.

CHANDLER: Right. Yep. Right. I, so the tools that I think, like I think about within our program and is in everything that we’re doing is progressions. Yep. Right. So when we’re teaching an eight year old to power pose, it’s like, so show me your Superman pose. Right. And then they all stand like that. That’s progressing down to when they’re 18. It’s like, let’s see this. Let’s see your power pose, man. Get behind that block, own it, right? That’s a progression. So it’s like, you know, the power posing is great. The yellow light, green light, our identification where you’re at is great. I think there’s a great opportunity at this age to start kind of laying the seeds of, of breathing, learning how to properly breathe. So like I would teach nine and 10 year olds how to box breathe and also belly breathe.

PERRY: We do the same thing. Like I will, like I said, this age, you can start, you know, running your kids through some like body weight workouts and like burning them out a little bit. Right. Like pushing, pushing them, making them winded. Right. It’s okay at this age. And oftentimes what we’ll do is we’ll do that. And then I’m all having like kneel down. I’m like, close your eyes. You guys know what to do. And then you hear just everyone go. And it’s awesome. Like how much under control that they do.

CHANDLER: Yeah. And you can utilize it for an anxiety tool or an emotional relegation tool or just a relaxation tool.

PERRY: I mean, I’ll do it in the middle of the match, which you can do in jiu-jitsu, like swimming. You’re like halfway across the pool, right?

CHANDLER: It’s like the pre-race.

PERRY: But jiu-jitsu, like it’s right in front of me. You know, a kid might be getting beat, smashed underneath the other person. They get mounted, which is like the worst spot and they’re defended and they’re safe, but they’re still in a really bad spot. I’ll just like close your eyes and breathe. Yeah. Because they’re like panicking. Right. And they’ll just be like. And I’ll just be like, you know what to do, right? I don’t say a technique to them. I tell them like, you know what to do. I’m not teaching you anything right now. Like, show me what you know. You got it. You got the control.

CHANDLER: Yeah. And it’s great, like teaching kids at that age, like those type of like breathing will, you’ll see it when they’re 16, 17, 18, where it’s like, that’s an automatic thing. We do.

PERRY: But like any, it’ll be automatic everywhere.

CHANDLER: Like everywhere.

PERRY: You’re going to catch that kid before a test doing their little Superman pose on their way to the classroom.

CHANDLER: Right.

PERRY: That’s the beautiful spot about it when you have a good professional coach that’s teaching these things.

CHANDLER: Yes. And, um, you know, we, we start introducing into goal setting and like, how do we formulate goals at this age? The whiteboard Wednesday does a great job of that, but like, what’s, what’s a performance goal. What’s a process goal. I like that. And like really basic, like give me your two process goals. Yeah.

PERRY: I like learning goals as well. Yes. Especially jiu-jitsu because there’s so many techniques. Like, hey, what’s one technique that you think you could learn and get a little bit better at that would have served you today?

CHANDLER: Right. One thing that impacted me tremendously as a coach, which would be interesting for you to go to, is I went to a seminar for sports psychology, and they had these tennis coaches talk about their tennis academy, which is based in Florida. And these kids are elite, and they can identify very young, that kid’s good. It’s like golf, right?

PERRY: I feel like I read a book on sport development, and there was a tennis academy in it. I wonder if it was the same one.

CHANDLER: So these coaches came to talk to us, and they gave us some of their basic foundations. One of the things that they talked about was their pre-practice and post-practice worksheets that they made every kid go through, and it started at like nine and 10. And I can send it to you, but some of them were very basic. They call them their ABCs, which is like, what’s your goal today in practice? What’s your ABCs today in practice? Have fun, learn something, right? That’s a very, for a nine and 10 year old, that would be a great thing to see. Like, that’s my goal today. And then they would go through like, what are your three process goals for today? Whatever they were, and they would list them out.

PERRY: Let’s give an example of a process goal, because I think a lot of non-coaches won’t necessarily understand what a process goal is.

CHANDLER: Yeah, well, I think that there’s, tactical, technical process goals. So like in the sport of swimming, I think process goals can be, there’s a wide range of process goals, but like in the sport of swimming, we’re talking about controllable, specific, positive-oriented things. So that could be something like, I’m gonna maintain four dolphin kicks off every wall, I’m gonna emphasize acceleration in my turns. In jiu-jitsu, it can be a completely different type of product. But what we’re talking, something that you can control, something that’s specific. not, we’re not talking about outcome based goals, you know, a lot of times with the athletes that I’m dealing with, they’re formally prior to practice, outcome goals of Yeah, I want to maintain this pace. Yep. That’s the outcome of you doing your process goes really well. Yeah, you know, acceleration.

PERRY: I do a lot like, you know, one big thing that I’ve worked with on my students is a lot of them tend to wait for the other person to go first. Because in jiu-jitsu, there’s a whistle that says go, but you don’t attack the person right away, but you can. And a lot of people wait for that. So a lot of my times, my process goal ends up being like, be the first one to do something. Or be the first person to get a grip, or something like that. I think those are really great process goals, and in my opinion, Those lay the foundation to actually winning.

CHANDLER: Right. Yeah. And I, you know, back to that worksheet though, is what I gained from is like, imagine if you set up your program where nine and 10 year olds, two minutes before practice, they start off before they even get in the water, they go into their sport, they spend 30 seconds, mindful breathing. And while they’re breathing right after that, they’re thinking about, all right, what’s the goal for day in practice? What would be like two things that you’re trying to accomplish? And then those nine and 10 year olds said something like, You know, we’re going to work on our turns, or we’re going to accelerate under our walls, whatever. Two things. And they did it on their own. Mindful breathing, so whatever, it’s box breathing, belly breathing, two minutes about belly breathing, power posing. Now spend a minute thinking about what you’re trying to do before practice. And they got on the water and they did their thing. And then at 11 and 12, they progress that. All right, we’re gonna spend a minute power posing, belly breathing. I want you to think about two things. And maybe the coach feeds it a little bit. But now it’s a little bit higher level stuff. And then at 13, 14, we progress it. And then by 15 and 18, they are doing it. They have their training journals. They’re writing down their process goals. They’re reflecting afterwards. It’s like, if you could set up your program like that, would your kids be better? Yes, 100%. And it’s that’s very hard thing to do. But if you put it into a practice scenario, like introducing mental performance tools within practice, yeah. And I, I think that you can do that at nine and 10.

PERRY: Yeah, you know, it’s teaching so much more than the sport. Yes. And again, we talked about like, Professional programs club programs, you know, are you guys at Schrader swim club? Yeah, you’re not much of a club You’re like a professional when I think of club I think of like youth soccer that me and you played right growing up with like just all the other little city teams and stuff like that with the volunteer coaches and stuff and Um, and I feel like you don’t get a lot of that in those programs unless those parents also went through something like that.

CHANDLER: The, and I, I also think that sometimes, yeah, and sometimes coaches, coaches sometimes are doing a disservice to athletes when they are like, it’s outside their scope. They don’t understand the harm. Like I’ll give you an example. We had a eight and under coach and this guy meant well, yeah. And he, He really cared, but he thought that it was a great idea to implement best time buttons. So if you win a best time, you get a button and then the kids would put it on their bags. Me thinking now, is that harmful or hurtful? 100% hurtful. When I go a best time, I get a button. Yeah. It’s a great thing to think about, but long term, what are you developing? What’s the value developing? Well, when I go best times, that means I had a good race. You can have a really good race and not go a best time. You also can have a bad race and go a best time. So if you’re valuing the outcome of this, every time you go, and I don’t get a best time button, even though I really had an executional race, no, you don’t get a best time button. So it’s like, this guy meant well, but unless you have this professionalism into thinking of coaching, of like, I’m developing athletes outside of swimming.

PERRY: Let the competition reward the outcome, right? if you win the competition, get a medal, let them get that medal. I think you as a coach and you as a parent need to reward that effort effort, the effort that came up into the competition and the effort that happened at it. Right? Man, that’s, I think that’s one of probably one of the biggest takeaways for parents is like, just recognize the effort that they’re putting in.

CHANDLER: Yeah. And the kids nowadays, like there’s so many external rewards. It’s going to happen. Yeah. They are already comparing to others. You don’t need to further that.

PERRY: Yeah. We just talked about it in our, in our pies, right? Socially they compare themselves to their peers. Um, man, what other competition things we cover just so much right there for, uh, this age group, what other competition things do we have for them?

CHANDLER: Um, you know, for us too, is like, this is the age group that some of these kids, and I think it’s an. We get introduced to national competitions.

PERRY: I think it’s also because you start getting outliers at these ages that end up being well beyond their peers. Yeah. When do you guys start? Is that this age group as nationals?

CHANDLER: Nationals can get introduced at 10.

PERRY: So we talked about when a kid should go from an in-house to a local, or even a regional sort of a thing. And typically if they’re starting at five or six, that’s when they’re doing their in-houses. And by this age, they’re doing the local stuff. My personal opinion still is if they come in at this age group, they should do some in-house first and then local. But how do you progress them at that 10 years old to the national level? And we don’t have to get into like national athletic development, but they’re at that stepping stone age where you’re going to get a couple of kids that are there.

CHANDLER: Yeah, and I think it’s very critical for kids, no matter the age group, to get exposed to people that are better than them. Like if you’re winning all the time, that’s really not good for you.

PERRY: You don’t get smarter being the smartest person in the room.

CHANDLER: Yeah, it’s really not good for you. So I think there is value to, all right, go out there and raise some kids that are better than you. There is a lot of value to that, but then there’s the loot of like, well, I’m not at the national competition, that means I’m not good, or oh, they’re at the national competition, they can swim at X school. For example, Michael Phelps was not good, like really good, until he was like 14.

PERRY: Is that when he grew to be super big and his hands the size of dinner plates?

CHANDLER: Probably, but also there was like, he was playing a bunch of different sports and he enjoyed the water.

PERRY: And as you should, as a kid that age, explore other activities.

CHANDLER: Yes. And I think that many parents early at this age, nine and 10 are starting to think about, all right, is this the sport that my kid is going to specialize in?

PERRY: It’s only going to get worse because WIA just allowed like year round contact with coaches for high school students. So it’s like when we were growing up, you had students at varsity at all four seasons in four different sports. You’re going to see a lot more solo athletes at the high school level, which is going to drive solo athletes at the middle school and going to middle school level.

CHANDLER: Yep. And, um, you know, I do think that there’s, especially in our sport where we’re in a different ecosystem, anytime an ecosystem, there’s a time for specialization, but at 10 years old, that’s not the time. It’s just not. And the more that you can keep your kid exposed to other activities, the greater chance they have for long-term development.

PERRY: Remember when like cross-training was like the big thing? Like everyone should be cross-training. It was like five or ten years ago. And now it’s like everyone’s just doing one.

CHANDLER: Specialized. Yeah. Yeah. And we got to get this trainer nutritionist and strength, you know, it’s like, What we’re trying to do in nine and 10 is to continue the progress of growth of having fun. And we know there’s going to be external things that are going to get thrown at the kid that are going to kind of limit that fun. So there’s going to be standards. There’s me a winner and loser. There’s going to be social comparison. There’s going to be bigger competitions. So as parents and as coaches, we don’t need to further that. We need to Like, limit how much pressure we’re putting into those.

PERRY: Man, so we hit pies, athletic development, a lot of approaches and awesome tips for kids this age, right? That golden age of athletic development, like they’re really starting to get it. They’re starting to get their first like real competitions consistently at this age. Last episode, we did a good challenge for parents. What’s a good challenge for parents that they should try to do over the next week with their kids in sports?

CHANDLER: I think the challenge as a parent at this age is to start creating more ownership with their kid. They are going to some practice because they want to. They get to decide. Start putting them more in the vehicle seat versus you. The more that you can do that, the more that you’re setting them up for success, which is similar to like the six and nine-year-old, or three, four, five, six-year-olds, like don’t interject. But you have to continue that, and now, and like, how do you create ownership within your kid in sport?

PERRY: I love it. I’m going to give the one of just praising the process. Praise the effort that they’re putting in. Don’t necessarily praise the outcomes. I’m not saying when they win, don’t acknowledge it. Yeah, of course. Give them a high five, but give them a high five and be like, man, all that hard work you did paid off.

CHANDLER: Exactly. You reward You know, the reason why you won today is you’re better than everyone else. You went out there and you’ve been working so hard and you went out there and you just went in and attacked it. Yeah. And I love watching you go out there and just racing.

PERRY: It seems so obvious, but us as coaches, the amount of times that we see the contrary to that is often.

CHANDLER: Yeah.

PERRY: Awesome, man. Well, um, anything else in this age group that we want to touch on before we wrap up?

CHANDLER: No, I think it’s a foundational age group. Awesome.

PERRY: If people are looking to work out with you, swim with you, do sports psychology, get some sports psychology help with you, what’s the best way?

CHANDLER: You can reach us at the Schrader Swim Team or clewis at wsacltd.org or championshipmind at chandler at championshipmind.com.

PERRY: The links will be in the bio description. whatever comes alongside a podcast. It’s a good one. Uh, it’s right next to the spot where you leave us a five star review. So please leave us a five star review on this podcast, share it with your friends. Um, but parents like a big tip, you know, when you listen to this, share it with the other teammates, right? Try to get the parents on the same page. We talk about how important the team’s culture is amongst the athletes develop a positive team culture amongst the parents too, where the parents are helping out the parents. Next episode, we’re doing like 11 to 14. Interesting one. You said that’s when Michael Phelps started specializing, right?

CHANDLER: Yeah, this is a big age group.

PERRY: Man, puberty starts kicking in. They can start getting into strength training. We started getting some volatile confidence challenges. I’m excited for that one. So 11 to 14, and then we’re going off to 15 beyond. That next level, a lot of times, what’s going to carry people to the end of their athletic career? Most people. But hopefully finding a way that they can even continue past that. So thanks for joining. It’s always awesome to have you on the podcast, Chandler, and excited for that next episode. 100%.