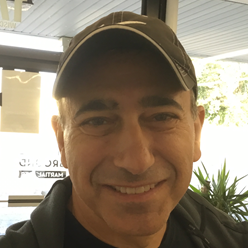

What happens when a strength coach with a background in elite sports, rehab science, and personal healing walks onto the mats of a jiu-jitsu academy? You get Keith Shimon—a specialist in muscle activation techniques, co-founder of Body Activation in Mequon, and a longtime practitioner in optimizing human performance.

In Episode 13 of Inside the Wave, Keith joins host Perry Wirth to share how his journey through fitness, injury recovery, and mental performance is helping athletes train smarter and stay on the mats longer. From working with NFL hopefuls to supporting jiu-jitsu students navigating aches, pains, and plateaus, Keith brings a science-backed perspective to functional fitness for martial artists.

Key Takeaways

- Recovery is training. Learn why Keith emphasizes precision in exercise selection for performance and injury prevention.

- Individualization matters. Keith explains why generic programs fail and how to identify the right stimulus for your body.

- Jiu-jitsu demands adaptation. Discover how Keith assesses load, control, and neurological feedback to optimize movement.

- The nervous system holds memory. Trauma, habits, and injury all leave physical imprints—and Keith breaks down how to work with them.

- Coaching is connection. Hear how Keith balances elite training knowledge with personal empathy, especially for hobbyist athletes and youth development.

💡 Bonus: Keith also shared a self-assessment guide you can use right now to get a clearer picture of your own movement patterns. Click here to access it.

Standout Quotes

- “The body is always adapting. The question is: Are you adapting in the direction you want to go?”

- “We don’t train for soreness. We train for stimulus and response.”

- “Jiu-jitsu requires control, not just strength. Control is what allows us to move safely and perform consistently.”

Where to Listen

🎧 Stream Episode 13 Now:

Connect with Keith Shimon and Body Activation

- Instagram: @keithshimon and @bodyactivation

- Website: Body Activation

About Utopia

At Utopia, we believe in personal growth through martial arts. Our community supports individuals of all ages, helping them challenge themselves, build resilience, and thrive both on and off the mats. Each episode of Inside the Wave aligns with our values of discipline, mentorship, and community, offering stories that inspire growth in every listener.

Why This Episode Matters

In a world of one-size-fits-all fitness plans, Keith reminds us that real progress comes from tuning into your own body. His approach is both technical and compassionate, showing that you don’t need to be a pro athlete to train with intention. If you’ve ever felt stuck, sore, or unsure how to move forward, this conversation is a must-listen.

Join the Conversation

If this episode sparked new ideas or helped you rethink your training approach, share it with a teammate or coach. Don’t forget to subscribe, leave a review, and keep following Inside the Wave for more episodes that bridge martial arts and personal development.

Transcript

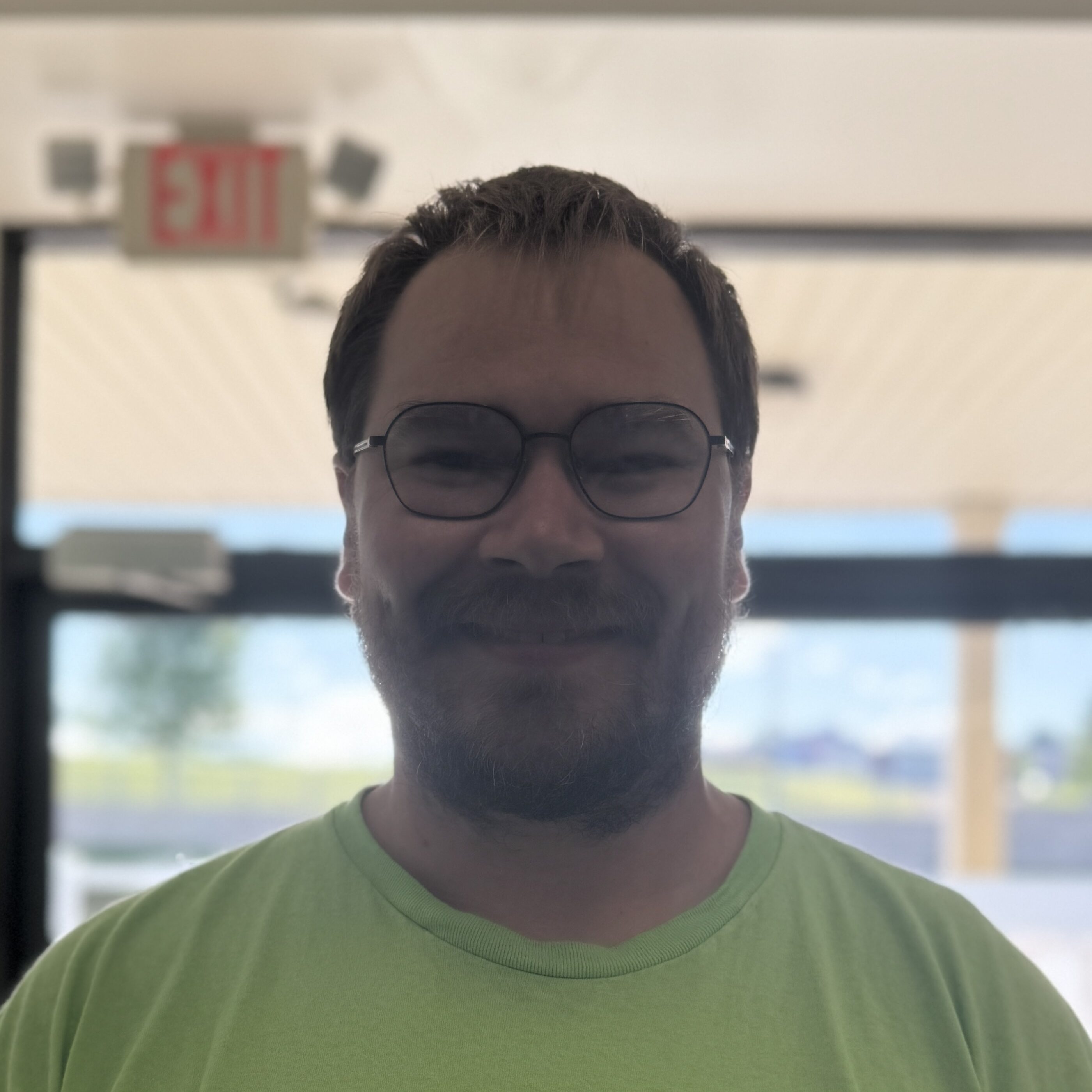

Perry:

All right, welcome to the latest episode of Inside the Wave. Today, I am with longtime friend, Keith Shimin. And Keith is the founder and owner, one of the owners of Body Activation in Mequon. I actually met Keith because he enrolled his son into our jiu-jitsu program years back. It’s been a long time, yeah. When was that, like 2018? That was before, that would have been like 2016, maybe. Damn, it’s been a long time. And I’ll let Keith give his background, but man, like, I don’t even know, people ask me, you know, what does Keith do? And I’m like, he just does shit that works, whatever, whatever’s effective. And it’s like, the thing I appreciate about you, it’s always changing. It’s always evolving, right? Like, you get new pieces of information, you work it in. But I like to tell people, at least in the terms that the average person knows, you’re kind of like where a a personal trainer, a physical therapist, someone who helps people heal, like you kind of live at the cross sections of those. But like, how do you describe yourself and like, what is your formal background?

Keith: Excellent question. My background, I started out in exercise and sports science at La Crosse University with a specialization in advanced strength and conditioning. So I went to school to train elite level athletes is really what my background was. I went to do a graduate assistantship at a place called the International Performance Institute, where I studied speed underneath Lawrence Seagrave. He’s basically the inventor of speed work in the United States. Like sprint speed work? Yeah. So people that want to get faster, he’s actually- I should probably hang out with that guy. He went to Madison. Okay, wow. So he actually got a degree in, I think it was chemistry, I believe. So but yeah, he invented these different techniques. He created something called speed dynamics I was fortunate enough to study underneath a whole bunch of elite level strength coaches there for four years Started a business there with with a colleague named Pete bomberito. He still trains Usually around 20 to 30 NFL combine guys a year and they have around 100 to 150 NFL vets so we’ve been in the the elite level training game for a long time. I broke off in early parts of my career, went back to massage therapy school, got my massage therapy license, went through the whole gamut of something called muscle activation techniques. And what’s interesting, it all led me to where I am now, which is exactly what you said. The crossroads of how does exercise help recover and restore a human is really what it is. And what I think people take for granted is this idea that they can just do random things that are healthy and they’re gonna get where they wanna be and that’s exactly what we’re gonna talk about today.

Perry: Yeah, so you’re talking about like your average person, oh, I should strength train two days a week, I should do some like long endurance, like, you know, there’s all these different, tools in the toolbox and you need to be using the tools correctly. Right. Right. And that correct usage might be different for me than it is for you or it is different.

Keith: Right. Well, there’s there’s a sense of overwhelm for a lot of people or underwhelm. Early in my career, it’s like we had Yeah, we were very fortunate that the tools that we used resulted in five years in a row of the fastest person at the NFL combine in their respected field. So it brought a name to our business. And it really took off. We were mentioned top 10 winners of the NFL draft by ESPN one year, which was really, really interesting, right. And But that led me to understand that you just can’t throw the whole toolbox at something. It’s about, are there signs? Is there a way to detect what it is you need when it’s appropriate? And that’s the toughest part of, of healing and also of recovery, but more importantly, of the word adaptation in what you’re really looking for is a stimulus and an adaptation when it comes to exercise. Awesome.

Perry: So you’re the way you’ve like gone about learning and gone about business that you’ve changed a lot over the years where I know you you’ve done a lot of like the elite athlete now you have a gym and Suburbia, Wisconsin, right? And you still get, I know you get MLB players in there and you go travel with MLB players, but like your average, your average daily Joe, that’s seeing you as a, as a client nowadays, like, well, what does that look like? And why did you go down, you know, kind of veer off the path of just specializing in, you know, professional athletes and kind of helping out everyone?

Keith: Well, I mean, if anyone with training athletes, you know what the hours are. Number one, it’s like usually what the way that those business models are set up is you got your beginning group that starts around 6 a.m. And then you have maybe some kids groups that come in. Yeah. Then you have the filler of the day with more clients than we had. We had colleges that we had our collegiate players came in that we did side contracts with. more pros that came in later. And then we had youth groups at night. So you’re going from 6am till about eight.

Perry: And you’re getting a you’re getting a spectrum of clientele in there, right? You’re not just dealing with like, because I’m sure there’s people out there that like I specialize in NFL linemen, right, right. So at least you’re you’re dealing with like, you know, probably running backs in different positions, but then also youth in different ages, which are eight years old.

Keith: Yeah, well, they’re starting eight years old. So we had one of the things that I studied in my undergrad was human development. So a lot of it was okay, what what type of stimuli is important? What levels of life? But then that started to shift when my father stopped breathing. So all of a sudden I was like, oh, this is not about elite level performance. This could be a life and death scenario when it comes to how somebody uses their body and all of a sudden they can’t, right? So my father, he was about, what, 20 years ago now. He was diagnosed with ALS. He passed away now 17 years ago. But it made a huge shift into me understanding how somebody adapts, how somebody may not adapt and then what may happen neurologically, orthopedically and or metabolically that would stop someone. So when would exercise actually help that and when would it just not? What could actually hurt somebody and make them not recover? Yeah.

Perry: So, and you’ve helped me on the spectrum, you know, we work out every Saturday, you know, looking to elevate my level of performance, but then you’ve also helped me keep on the mats and stay in performance, but also get back on the mats after injuries, right? Like, you know, in the sport I’m in and being in grappling for so long, you know, everyone’s life takes a different toll on each other. And And that’s something I’ve learned from you, like you could have stubbed your toe when you were six, and that can show up when you’re 35, right? Like, yeah, that your body holds the the trauma behind events that I mean, you hit the nail on the head.

Keith: Something that’s been very apparent recently is the idea of there was a book called the body keeps the score. And that that that really set the tone for how is the body learning through trauma. So it learns really quickly. And What we’re aware of versus what happens below the radar non-consciously. I’d say a majority of life is non-conscious. Where you don’t have to worry about breathing. You don’t have to worry about pushing red blood cells through your body. You don’t have to worry about your heart beating. You’re just aware of what the day-to-day is and how things change. What we look for are we look for tells look for what is your body trying to say? What is it trying to do? And we’re just taking better notes than a majority of people that are in our industry where it’s like they’re they’re making assumptions about things that we just don’t believe are happening. And that comes down to when something is hurt. It’s now modified. It’s not like it’s going to go back to what it was. I think it’s permanently modified and now It could end up that when you now have a change in it, it may not have been that strong to begin with. It may not have been that calibrated to begin with. You may not have had a lot of tissue genetically and predisposed to it. So it’s like, okay, what can we make it now? And now what’s the other side of the coin where it’s like? how optimistic can I be? Like Greg Lehman says, uh, what is my movement optimism? What can I do right now? And if, if you can shift towards what can I do right now, you can get granular with it and use exercise for what I believe it’s most powerful aspect is now. And that’s why we’ve reduced everything to exercise rather than massage and all these other modalities is because I firmly believe that exercise is the only modality that can build tissue and help you learn to move through space.

Perry: Yeah. Can we, and I’m sure you have a great definition of it, but can we define what exercise is?

Keith: For sure. I mean, it’s a very simple definition that I like, and there’s so many complex definitions. It is when you provide a stimulus or take a stimulus away to create a specific adaptation.

Perry: I get adding a stimulus, right? That could be like putting weight on something or even engaging a muscle, right? Would that be a stimulus too?

Perry: Yeah.

Perry: If I just sit here and I flex my biceps at the camera. or your intention. But what is taking away a stimulus? Like what’s an example?

Keith: Yeah. So say when somebody comes in, and they’re like, well, what’s your day to day like, in every day, you are doing a job where sit out of the computer, just sitting like that. Yeah. Okay. Well, what if you stood up? Yeah. And then sat down? And then you decided to stand on one leg or you walked on it, right?

Perry: So because I am sitting at a computer all day, there’s likely certain Muscles and parts of my body that I wouldn’t be using like they would like they were meant to be used, right?

Keith: Because the only thing that we’re really looking at is how are you holding your body in space? And how does that relate to how you feel?

Perry: Awesome. So let’s talk about why you’re just real quick, I want to give an overview of why why I’m having you on the podcast, because I think this is a really great point, right? You’ve you’ve trained like, the whole spectrum from focusing a lot in elite, elite athletes to people that are really struggling in their lives. So like hip replacements to do anything, right? In our world of jiu-jitsu, most especially adults, right? And I know you deal with youth too. And we can we definitely touch on youth. But like, typically adults are 3540 have an exercise in years looking to get into jiu jitsu. So like, that’s one stage, right? And then we get people that are starting to do jiu jitsu that, you know, they want to be able to get into more different positions, right? They’re not, they haven’t injured anything yet, or maybe they’re injured, and they need to come back. But, you know, sometimes you see a move, and you’re like, I just can’t get my body into that position quite yet. I’m not strong, I’m not comfortable, whatever it might be. But then you also get the whole peak performance like hey, I’m getting ready for a competition I want to go win a tournament whatever it might be and I think there’s a very broad spectrum that we can talk about But but I would love to touch on kind of you know bits and pieces of all of those you look into like that certain journey of an of an athlete from I think that like we’re a majority of the people that come in and and

Keith: what they’re really looking to do is there’s something that’s keeping them from doing the thing that they love, right? So number one, it’s defining what it is that you wanna be able to do. And what somebody wants to be able to do usually has a motion to it or a position, right? So and if those positions aren’t controlled well, people are gonna have problems. What do you mean by controlling a position? Fantastic, I love it. So in jiu-jitsu, how do you get somebody to submit?

Perry: over extension, over rotation, tickling, or like choking or, yeah, asphyxiation, right?

Keith: So anything that renders someone incapable of control, right? So they can’t control their bodies with either blood flow or they’re beyond the control continuum of the materials of their arm. Materials being skin, ligament, bone, tendon, all that kind of stuff, right? So there’s a certain spectrum that everybody has control over. What we use exercise for at any level is to try to define that continuum And then it relates to the person of how they feel as they’re going through those control continuums. And what’s really cool is that you can take very simplistic structures and say, well, if I’m going to bend my elbow here, this is the load I can use. This is how long I can do it for. And this is how I felt in the next day. This is how I recovered. It’s really simplistic, but there’s also a ton of variability, which gives you even more transfer to everything else that you want to do. Because if you’re not going to use it, you lose it.

Perry: Got it. So, so maybe it’s a good example and maybe you can help me like quantify this, but I’d actually just had a. We did combat week this last week at our gym where we do jiu-jitsu, but we put on gloves, we use fake knives, and we take jiu-jitsu back to like the self-defense world. Getting all stabby. Well, we’re all jiu-jitsu athletes trying to do all of that other stuff, right? So it’s really challenging for… For someone, especially if they’re not that good at jiu-jitsu yet, they need to try to think about everything versus just jiu-jitsu. It’s hard to focus on 18 things at once. It’s like running while throwing a baseball and swinging a bat. It’s hard to do if you don’t know how to run in the first place. But one of my students came to me and he’s like, dude, man, my lats are so sore from class last night. And I was like, I don’t know if I’ve ever done jiu-jitsu and have had my lats get sore And I’m like also we’re doing you know, most of the class because we’re doing punching There’s a there’s a lot of extension in that class, right? Not as much of like pulling a lot of times when we’re wearing the gi we end up pulling on the uniform a lot but it was no gi and I was like, wow, why would this guys I lats be so sore after a class. And is that because he might not have as much control over that as normal? Is that a way for him to identify a weakness that he should be working on? No, that’s a fantastic point.

Keith: There are so many different pieces of control continuums. And the way to identify it, number one is having having a method to debrief what’s going on, right? So exercise is one way to debrief positions. It’s like, okay, this arm is doing great with this curl. This one not so good. Yeah, I’m bringing my arm out to the side. That’s okay. That’s not so okay. If I recover, What did I do the day before and does that relate to soreness in specific positions? But also remember that control is also about how we detect our environment. So eyes are gonna matter. Hearing is gonna matter. like mouth control, TMJ is going to matter. Your inner ear is going to matter. Your hands and your feet, the sensors on there, they’re going to matter because it’s all combining of how you’re taking info from the environment to create a solution. And how you recover from that solution is going to be your adaptation. So it can be complex, but to simplify it, it’s like, Man, I got to try to make something repeatable. And that’s why I like having a grid, something really simple to do of being able to then flush out that information to see how I’m controlling it. Lastly, most people try to shove themselves into positions. That’s why I’m in such a huge favor of trying to control loads in positions rather than the stretch. it’s not really any different than overloading the end range in a in a submission. So if you want to train, getting like submitted, great, then I can overcome an arm bar or whatever. But it’s like, if I want to then have strength in that range of motion, I better load it. Yeah. Okay.

Perry: Yeah. I mean, there’s a lot of, um, I mean, maybe not a lot, but there’s a lot of spots in jiu-jitsu where you’re like at that tipping point of a submission.

Perry: Right.

Perry: And, and hopefully you can see the other side of it without a getting tapped out and be walking away with a minor or even major injury. Right. I know escapes, we have one from an armbar that’s called a hitchhiker escape, where someone’s trying to get my arm straight, I’m holding it, and I actually let them get it straight, but because the fulcrum’s here, I’m gonna turn my elbow and roll out, so they start bending my arm the other way. But there’s this split second where I need to be able to bear that load, or potentiality of load, till I can roll out.

Keith: Or it’s going to get bent to a way doesn’t bend.

Perry: Yeah.

Keith: And then that’s, that’s exactly what I’m talking about. So the simplicity of it, you don’t have to be have like a PhD in physiology and anatomy, to know exactly how your body bends.

Perry: I tell people that all the time, like, you guys know, elbows, primarily forward and back, you know how you win jiu jitsu. make it go further than it’s supposed to. Like, you know how your shoulder goes?

Keith: Just make it go a little bit further. But who’s training? Who’s training internal rotation? Yeah. Like who’s who’s training going all the way across the body? Who’s adding torso rotation?

Perry: I mean, think about if you think about your average adult doing sports, right? Whether it be tennis or golf or Jiu-jitsu being complex. You have adult hockey, which is terrifying. Whatever it might be, most of those adults are just training their sport. If anything, they’re also just lifting. But it’s like a standard lifting program. It’s very standard. It’s like your bench, your squat, maybe some unilateral machine work and stuff like that. But to your point, you know, if people are training flies, they’re probably just flying right here. But you’re talking about like, I should be going through different ranges that we might see in our activity.

Keith: Yeah, it’s like, why are there any types of rules when it comes to exercise rather than exploration? And then observing what happened, right is what the process of writing down just like we’ve done it and lifted before is so powerful, or it’s just writing something down, like having a process to know what happened previously, so that you can, you can expand upon it. Yeah. And because I can’t tell you how many times I wish I wish I got paid every single time I asked this question was like, Okay, so what do you do for exercise? And like, why run? Yeah, I bike and I’m like, uh, that’s not exercise. That’s an activity. Yeah fun. You can get fatigued What is your specific adaptation from the stimulus that you want to have? Hmm. It’s because if you don’t know then you’re just, you’re just biding time and you can be very enjoyable and it can also be healthy. But like, what if there’s an orthopedic problem on the knee and you got to get your, you got to get your biking in or you got to get your running in and you’re going to turn that thing to powder. Like once the joint is gone, it’s really hard to keep going.

Perry: how do you, you know, most people walking around, right, they know their painful weaknesses, right? You know, what’s achy, what’s sore? You know, what, what they heard in class the other day, right, whatever it might be, and I feel like those are the obvious ones, but working with you, I know that those usually don’t end up being the ones that matter as much as these hidden weaknesses. Oh God, what’s a good example of me, right? Like, you’ll have me turn my head in one direction and I’ll go weak. Yeah, yeah, yeah.

Keith: Okay, my foot. Your foot healed this past Saturday, right? So yeah, there is a hierarchy, right? And anyone saying that the different parts of your body heal at different rates.

Perry: Yeah.

Keith: If they don’t know that, then it’s like saying, well, I’m gonna wait for my tooth to heal.

Perry: Yeah, so how do you like identifying these weaknesses that we might not be, aware of, right? Because like, you found the weakness in my that started in my foot. But it only took 30 years to get there. Yeah, but but there’d be like, there’s no way out ever been like moving around at the gym and be like, Ah, it’s my foot that’s actually making my knee hurt when I squat.

Keith: You might though. And that’s why it’s like having that whole grid process of like, okay, when am I going to do single leg plantar flexion, calf raises on one side weren’t blocked at the knee versus standing? When am I going to do single leg knee extension? When am I going to do single leg knee flexion or or leg curls? Yeah. What am I going to do and parse out this stuff to see if I feel it in a different place in my body? Because if I feel it in a different place in my body, they’re neurologically connected because you’ve perceived them. That’s the only way you can perceive it if it’s neurologically connected. So then if I’m looking at manual resistance now, strength training, with me using my body as the exercise device, I can see how well you can control it by just pushing on it. Like, can you hold it here, right? And if you can’t do it, and your whole body changes how it tries to recover, you’re gonna feel it. You’re gonna feel that. You’re gonna be like, wow, this is not really that easy to do. So yeah, there are definitely hierarchies in a body that is a whole separate idea. Just putting it very simply, think about if you’re gonna use your feet, is it the same sensation you would have if somebody were to touch your tummy? or your belly have kids, right? Yeah, that’s your belly versus touching your face. Sure. Versus your hands touching something. It your brain almost automatically can tell you okay, this is a can I could close my eyes and I could hold the can and be like, Oh, that’s a can. different sensation, different neurological linkage, different results. So hand injuries are not the same as foot injuries are not the same as I injuries are. They’re different materials, they have different sensors, and they’re going to do different things to the body.

Perry: So is this why is it? super random. But I was just thinking about people doing doing air squats. When people start doing a lot of air squats, their hands will move around, right? They might be here, then they’ll move to here, then they’ll move to their belly, then they might move them up. is that because it’s actually causing change and like, you know, me moving my hands around and what my hands are touching or not touching and how they’re positioning my shoulders is actually affecting something within my legs while I’m squatting.

Keith: Well, I mean, that’s a huge opportunity, right? So anything that you change, there is no such thing as a real repetition that can be repeated. There will never be a point in time where you’re the same person that you were doing one rep and completing a rep as the moment before, even like the part of the rep, you have different cells that have since lived and died, that have to communicate to each other. And the only thing that’s pretty much the same are gonna be your neurons.

Perry: So- So in reality, if you do one set of 12 layer extensions, really all you have is 12 completely separate reps that have built upon each other that have created an average and that’s typically what people take at the end of it It’s right I did I did 12 single reps average, right? but you might have been looking to the left for one of those reps because Someone just walked in the gym and you know that last rep that gets really hard You might have lifted your head up right or you might have bared down on something and you’re actually changing

Keith: changing the intent, how your body is that right completely. So if I decide to go up, you’re talking about how am I spinally extending? How am I extending this whole thing? And then how does it relate to this leg control? Because if I do one leg, that’s what I also have to do. My body’s controlling rotation and extension is controlling all these other pieces. So what we believe in actually what what we have seen in the literature is something called peripheral nerve trauma. So if you hurt a nerve, it’s a very loose term, right? Because what’s really cool about a human is you have you start out as this like one cell. And then all of a sudden, you just grown out of double and double and double. Yeah, you just keep growing, right? So your materials are grown out of each other. So they’re embedded These nerve cells are embedded in all these other tissues. If you sprain an ankle, if you tear something, if you strain something, that could be a peripheral nerve trauma of which now that original sensor that was saying, hey, this is the info that I gotta pay attention to may not be connected to the original neuron that it was connected to. So it’s like, oh, I gotta relearn this somehow. And that’s why learning positions under load and seeing what happened can be so valuable for people.

Perry: So to get, To get some tools in people’s tool belts, you know, what is one of the best ways for a jiu jitsu person? You know, you’ve worked with me for a long time. So you know, a lot of the positions that we get put in, you’ve watched a lot of jiu jitsu. What’s what’s one of the best ways for us to do a self assessment or debrief of our weaknesses or even find strengths at that point in time? Yeah, I already have.

Keith: a whole Google Doc created. So I’ll give you access to that Google Doc and your entire. We’ll put it in the notes. Yeah. And then from there, we can put together how I would actually debrief it. OK. So and what I would pay attention to so that they know exactly what I’m thinking about. And remember, every one of those exercises is a construct. So it’s about how it relates to you. This is only They’re only described as try this is an invitation to movement and that’s why inviting yourself to explore what you’re capable of Start slow start controlled and start light and then start testing yourself and keep modifying it I think a big takeaway for me is like How unique everything is to every person.

Perry: Yeah, like me and you might have a this, a similar injury that’s diagnosis, the same injury, right? And we’ll use a very common one in jiu jitsu, like a medial meniscus tear, bucket handle, medial meniscus tear, super common and in jiu jitsu and a lot of sports, right? Um, if I had it and you had it, you know, a doctor, my diagnosis with the same injury, but the way our bodies perceive that injury and the weaknesses that it creates given the map of the world that our bodies have and that they’ve come from is totally unique, where there might be something because it’s a similar. mechanism of injury, right? There might be some things on average that will work for both of us, but there might be some very unique things that I might have to do because I also turned my foot into a taco at one point in time in my life. You could punch people with your toes? Which happened once. No, I can do that. I can take my foot and like curl my toes and make it a fist. I can stand on it. like a monkey, but actually threw someone and my foot was like on its side and it collapsed in on itself like a taco. Yeah.

Keith: Yeah. And it what you’re what you’re talking about is, is what is referred to as mapping. So in a human, there are several maps within your nervous system, which is supposedly a representation of how your body would how your nerves would control those parts of the body. And a majority of it is, I mean, I think there’s like seven maps that I know of right now. There’s like some in the spinal cord, there’s some in your brainstem, there’s some in your cerebellum, some in the sensory cortex. There’s all these different places and they all have to like talk to each other. And they’re all based upon your history. And we talked about that allostasis, like, what is someone’s cumulative trauma through life? Or what what are they used to doing? Because if somebody comes in, they’re used to training, I’m not going to treat them the same as someone who’s just starting out who’s terrified of lifting a weight. Yeah, it’s just not the same, not the same organism, right? Not the same stress level. It’s just not the same. Yeah. So then what we do is we’re trying to find that baseline of where do we start. And the most simplistic ways to start is going to be to organize how you move and how you feel. And anyone can do that. What I do is I try to find how all those other pieces of the nervous system and how your physiology line up towards creating the adaptation that you’re looking for in way less time. I’m like what people spend months doing may sometimes, sometimes, not all the time because it depends on what was damaged. But if it’s a control problem, we can do it in reps would have taken months. Yeah, and other people that that that are involved in this podcast already felt that and then we have not only are we giving it the random 10 reps three sets kind of stuff. Yeah, we have we have specific loads that we’re looking at. Yeah, we have specific rep ranges that you’re tolerating with the specific load and we know exactly how long the rest period should be because we actually time them.

Perry: Yeah, and even like speed of rep, right? Like the eccentric, the concentric, the isometric.

Keith: We time how long it takes you to complete the set. So we have a breakdown of this right one is doing this many reps in this timeframe. So we know the reps per second, we know the pounds per second, because that is also rate of force development, which you’re going to need if you’re going to have any power expression or velocity. So it’s like we know the metrics that we’re looking for, which most people are not looking for in our space. Yeah.

Perry: Interesting. So we’ve talked a lot about like, you know, identifying these weaknesses. And we talked some about body adaptation. But what about like, just monitoring your own training, your own progress, your own recovery to prevent some of this stuff.

Keith: Oh, for sure. I mean, I’ve been there in my youth as well. I’m like, the stronger I get, the better I’ll be. And I can tell you, I didn’t feel any worse than when I was at my strongest. Like I was lifting my heaviest loads. I was fortunate enough to work with some people that that trained at Westside. So I learned a lot of like different Westside methods.

Perry: I mean, you definitely see there’s a there’s a give and take. Like I know I’ve known a lot of power lifters over the years that they’re like, they’re super strong, super strong with their blood pressure and resting heart rates through the roof.

Keith: Right? Right. And it’s like, so how do I feel? Okay. And what’s really cool about humans is that you’re innately going to know if you’re okay. Yeah, like, how does somebody even know that they’re, they’re okay? Yeah, like, all of a sudden, it’s just like, Oh, I’m okay. Well, how do you how do you know that?

Perry: Right? But it can it be like, one of those things, too? We’re like, you know, I feel fine. But if a doctor asked me, like, Hey, how do you feel? Like, how do your shoulders feel? Like, now that you say it? my shoulders feel a little like stiffer than normal.

Perry: Feel stiff. Right?

Perry: Like where a lot of times you think you’re okay, but then when you truly think about it, like how does my knee feel? Yeah.

Keith: And so that’s the other observer, right? So when you’re observing yourself, you’re only capable of dealing with the information that’s coming in to say like, how am I debriefing and feeling, right? When you have another observer, that’s another benefit of having a coach. Right? Any coach at all. The whole point is you have another observer to ask you questions, to dig deeper about problems and solutions. That’s all that’s really happening. So when we’re looking at, okay, my own training. Number one, what do I want to have happen? If I want to, if I want to be able to do this thing, right? Like I want to be able to say my whole goal is to be able to keep my hips healthy for a lifetime. Now I have a time frame. Now I know that I have to be able to handle a whole bunch of different positions. Do I really need to be able to squat 500 pounds? Probably not. Right? If I need to be able to do my daily workload, what is my job? Like what am I picking up? What do I have to be able to tolerate? And can I even tolerate that? So first is the fundamental objective. What do I want to be able to do? So now I’m aligning all of my training to do that stuff in those positions for that timeframe at that load.

Perry: It’s like, hey, I know I’m going to want to do Jiu Jitsu. I want to do Jiu Jitsu. I know that Jiu Jitsu is going to put me in vulnerable positions I want to survive in, right? That could be like extreme spinal flexion. It could be extreme like spinal rotation. Yeah. But like, how do I you know, and it’s very dependent on how that person plays, you know, just like how, how you’re talking about how unique everyone’s body is, like everyone’s jiu jitsu is totally different. Yeah, like, Big 225-pound dude, probably not getting stacked very often because he’s effing huge, right? Big dudes that have huge bellies are actually hard to stack because their belly stops them from flexing so much, right? So fat dudes don’t get stacked that much. Their load’s going to go to their head, though, right? So everyone is different. I think we kind of look at our own jiu-jitsu games, especially experienced athletes, And we can look at like, hey, based on how you play in the positions that you like playing, like this is different.

Keith: Who are the best? Who are the elite of the elite in almost any sport? The people that are freaking out and stressed? Yeah, people that are cool, calm and collective.

Perry: Yeah.

Keith: Right. So what we’re talking about is patience through a process of observation and being very specific when there’s no real guidelines and no strict regimens. How do you become the best at jiu-jitsu? Is it just one path? There’s never just one path. So then it’s like, what are you hoping to do? And then from there, are you okay discovering stuff? Because do people believe that, normal people believe that I found is that their idea of how quick it takes for a transformation or recovery to happen is such a compressed window. When if you ever heard a ligament, that’s like three to six weeks minimum of like, even having that thing recover at all if it even recovers. Yeah. So knowing those types of timelines, setting those expectations, so if you can’t load that stuff correctly, you could be doing more damage than good. But if you start light and you start controlling it, you’re going to be really good. But if you’re moving fast, It’s like saying, I’m going to take this weight, right? Because people think that five pounds is five pounds. I’m going to take five pounds and set it on your hand versus throwing it on your hand.

Perry: Have you seen the Punisher when he, when he, like the guy’s dying and he puts a grenade in the guy’s fully extended hand and pulls the pin and just walks away and he’s just holding it a grenade. And the Punisher knows like the guy’s going to drop it and make himself explode. But it’s like five pounds up here is way different than five pounds. And I will give you the perfect example. I used to Peloton a lot. I still love Peloton-ing. And there’s some like Peloton workouts where you use the little like dumbbells on it. And they’re like, you know, the dumbbells come in like one pound, two pounds, five pounds, seven pounds. I’m like, I’m getting a seven pound one. It’s like seven pounds. It’s nothing.

Perry: I’m like, I’m like, I want the two pound ones, please. Cause they’re like holding it.

Keith: It depends on, it depends on where you’re holding it. It depends on if you’re accelerating it. Yeah.

Perry: So like what’s like, hold it out. Here’s one thing. Okay. Now do little arm circles. You’re like, Oh God.

Keith: I mean, it’s like people are like, okay, basic physics, right? Work equals force times distance. Yeah, if I have a lot of distance, yeah, like I got I got to really come up with some force.

Perry: Yeah, right.

Keith: Because it’s a multiplier, acceleration, and thinking of what weight is. What is weight? It’s mass times gravity. Gravity is an acceleration. So the faster you move something, once it hits another object, the force becomes very high. So it’s like understanding that, hey, if I move things slower and I start closer to my body with control, with lighter loads, and then gradually work up, I’m going to be pretty safe with stuff.

Perry: What are some of your favorite ways to like, I guess, qualitative and quantitatively assess your recovery, right? I know everything from like, you know, doing a body scan, right? Yeah, my shoulder hurts. I like doing NSDR a lot, where like a lay down and actually do a body scan, like starting at my like, big toe. And I’m like, Oh, I actually think about how my left big toe feels right now. Right? Everything to like the latest crazy like heart rate variability and resting heart rate averages and the push for blood work and all that stuff. Like what are your what are your primary ones that you look at at like a daily basis? And what are ones that you maybe look at over a longer period of time to assess like, how is my body doing?

Keith: Yeah, great question. I’d say that the first thing that I like to categorize is a laundry list of my injuries. It’s usually where my control is going awry. I mean, you’re talking about like injury since the dawn of time, correct? Okay. I mean, put it this way. It was like I had, um, a lack of ability to control my recovery through my right foot, because I fractured it when I was four, and I didn’t discover it until about two years ago. So I’m like, Oh, this, this, this is healed. I mean, this is no problem. I, I can jump easily off, I can move well off it, but my my recovery for endurance wasn’t there. So like, remember, there’s there’s force output, there’s position, there’s the endurance of it, and then there’s the recovery of it. And then there’s like power and speed. So it’s like, if I’m looking at these things, it usually starts where there’s been a trauma. And very rarely has the information how I control that area has that recovered. And remember, because when people are like, oh, it’s all connected, they believe it’s all connected until their shoulder hurts. Yeah, you know, I’m just like, that really is all connected. That was proven a long time ago with basic, basic neuronal experiments from Sherrington, Sir Charles Sherrington in like the late 1800s, to the early 1900s, where he, he like stimulated part of the neuron in like the whole nervous system lit up, right with the way that he was, he was looking, I feel like your body, use an analogy that

Perry: Maybe someone’s used it before. I feel like your body in its life is just one giant chess game where every single move you make Matters at some point in time.

Keith: It’s a memory-based organism, right?

Perry: So everything that we do is context based upon memory, even if it’s non conscious Yeah, and it’s not like hey you get injured you recover and now you’re starting a new game.

Keith: Yeah, right It’s like it’s you’re always saying you’re always saying one game though like yeah that that’s what I think it’s more accurate to say like each day is Yeah, you have. Yeah, I me right. I have this memory of me being me or whatever, but you’re still not the same person. Yeah. So it’s like there are these unique challenges of okay, I’m going to look at how my body is holding on to memory. Think of it like tissue PTSD. What was the the trauma that was that was Helping me learn to stay okay, because it comes back to two separate things like our body’s always gonna want to conserve calories So it doesn’t starve and it has to move about its environment. Yeah safely so that it doesn’t die, right? So everything that I’m doing is okay. I know that trauma is like one rep learning and I mean, it takes one rep. You stub your toe, you don’t have to learn to like hop on your other foot. You just instantaneously learn to do it and like, okay, there’s a solution, right? So what are invitations to new solutions around the traumas that I had? So number one, I look at my previous trauma. Number two, I see how do I move now? What is my load capacity to be able to handle doing something? Did it feel okay? And then overall, what would happen the next day? So if I’m using those, then at least I have this idea of strength, endurance, control, and then how it relates to things that maybe I lost ability to detect accurately. So and that’s really what happens with trauma is I think we just don’t detect it accurately. So what we perceive isn’t really what’s happening. Yeah.

Perry: So based on all that, how how is it best for a very, you know, let’s say a novice? exercise or a novice human, what’s the best way for them to approach the whole gamut of exercise? Everything between whether it be strength training, speed training, mobility. I know we’re not fans of stretching. Making sure you have control on that. What should your average Joe look to do if they don’t have access to someone like you to help out, right?

Keith: I think two things that I think are tremendously important to quality of life. Number one, know your blood pressure. I mean, if your blood pressure is elevated, you can do some serious kidney damage, some eye damage.

Perry: And there’s like serious ways to actually measure your blood pressure. And I heard, I think Atia, Peter Atia on this one. It’s like, when you go to the doctor and you sitting in the clinic and then you get up and they walk you to the room and you’re like, sit down and check your blood pressure. It’s not an accurate representation of what your blood pressure is. You’re supposed to be like, do it first thing in the morning. You’re supposed to be calm, sitting down for 10 minutes straight, feet flat on the floor, hands like- Repeatable too. At a certain spot. and then take your blood pressure.

Keith: Same time of the week. Yeah. Same day of the week. Yeah. And I’m also a real big fan of that being a blood draw too. So a regular CBC or CMP, if you’re going to have your annual done by your doctor, what is something called your hemoglobin A1C? Something to know exactly how your body is dealing with sugar, right? Because blood sugar is a really important factor for recovery. And then also, if your body is not metabolizing fats well, because that can end up in stroke and heart problems, right? And that can happen as early as like mid-30s to 40. So it’s like, if we’re really playing the long game, it’s like, oh, here are things that I do. Blood pressure is something where, okay, make sure that you check your blood pressure every once in a while. Make sure that you’re doing your blood work at least yearly, you know, so that you have an idea of how it’s changing over time. And then literally the grid system that we’re going to be sharing with your audience is what I give all of my clients when they’re out of town and they can’t actually train with me. It’s the debriefing system of, okay, do these things, list what happened. And now from here, is there any really huge discrepancies? And there’s really simple ways to start making those discrepancies hopefully a little more symmetrical or is there a trauma reason where they’re never gonna be the same like a joint replacement or a major surgery or concussions or traumatic brain injury, right? Those things may permanently alter how somebody perceives their environment.

Perry: What is your approach on But we’ll just classify it all as just workouts in the gym, meaning like. A new person, a novice lifter, someone that’s maybe been lifting for one or two years, they know the general mechanics of your standard exercises. They’re knowledgeable on how to use a preacher curl machine. They know how to bench press, at least at a safe novice level. They’re not a power lifter or an official Olympic lifter. But what’s your opinion on finding a program online, like a generalized program, and maybe Because they’re novice, they can make substitutions like, ah, my back hurts when I deadlift, so I’m going to find a different way to work my posterior chain or hamstrings or whatever it might be, versus just coming up with a program and going to the gym and playing.

Keith: Yeah, I’m a I’m a huge fan of context. Okay. And so any way to build a knowledge base of just what you feel safe with what you feel comfortable with. That’s, that’s the key to doing right. So starting by even doing two exercises or one exercise, And then doing that daily, where you’re just changing your exercise. And like maybe a week from now, I’ll do that same exercise and see what happened. And then I’ll just do another exercise the next day, building these habits, right? Because if you’re not fatigued, you can do you can exercise every day, right? And as long as you’re not just blasting yourself with fatigue, you can play on different exercise pieces or with a dumbbell in different positions daily. And I highly recommend starting with some machines where you can ask someone how to use the machine, right? It just, there’s a lot of people in the gym usually to point you out how to set something up and do it in a way where you feel comfortable. It if you’re taking action, because you believe I need to be able to move better, how am I going to practice moving without moving? Right?

Perry: Or at least sit sitting still and resisting something that the struggle that I’ve always had in the gym is like, I love, like progressive overload, like linear training plans, where every week, I’m either going up rats, or I’m going upsets. But I also like the play side of things. The challenge is, is like, the progressive overload doesn’t give me the play. And the play doesn’t give me the context of, you know, at least by the numbers, am I doing better? It gives me like the, am I feeling good? And does this feel good? But it’s not like, am I improving? It’s very hard to quantify, right?

Keith: So. Yeah, I think it’s important to have both, like quality and quantity, right?

Perry: Yeah.

Keith: how does somebody know something’s better without being asked, is it better? If you just look at the numbers and say, man, you’re doing great. And they’re like, awesome. They’re limping away. It’s like, wow, you did. You just killed that squat, but you can’t fall asleep because you’re in chronic pain and you can’t you can’t move your hip. Right. So I would say that the quality and the quantity are just as important.

Perry: Yeah.

Keith: So if you’re if you’re going through a linear progression, or say you’re one of my favorites, right? The hint to Travis mash on this one. Yes, he’s, he’s doing a project of more than I’m a huge fan of, but he’s also a fan of super training, which is this one book from from the past of Mel Siff and Uri. Yeah. So, Virk Oshansky was one of the creators of something called block periodization. And the block periodization plan was like, okay, we’re gonna do all endurancy work like this, we’re gonna do power work like this, but each power block had its own progression in either total upper or lower extremity, each velocity one had this type of deal. I think that’s how Juggernaut approaches their program. Virk Oshansky was supposed, could be right. I don’t think it was Vladimir. I think it was Verkhovsky that was one of the pioneers of that approach, but like how they then said, what’s your readiness state? And we’re going to do this plan. And we have a progression for that plan. It’s all based upon where you feel you’re at right now to make sure that you can, you can get the adaptations you’re looking for in the readiness state that you’re at to not waste time. But that’s, that’s, that’s an athlete based approach. If you want to help with performance, if we’re talking about just getting started in exercise, you’re talking about feeling comfortable with what you’re doing, making sure that eventually you can do one set. A set being an organization of multiple times of doing that, the repetitions, right? So that’s the organization of the set if people don’t know what a set is versus a rep because that can happen. And then the frequency, how many times a week do I want to do this? If you’re a little more trained, chances are you’re going to do two, two to four times a week of resistance training, starting out around two times a week. Pretty good start. Yeah, because it’s a lot more than what you they were doing previously.

Perry: Yeah.

Keith: So how

Perry: you know, no matter your training, you’re bound to have some sort of incident happen. And there’s a broad, broad spectrum of sports.

Perry: Yeah.

Perry: There’s a broad incident of things. Um, you know, everything from just like discomfort.

Perry: Yeah.

Perry: to, to major injury.

Keith: Um, and all the bone jetting out of sideways.

Perry: And we were just talking about my friend Steve, who was on the podcast and he dislocated his toe once in one of our old mats. And, um, it actually dislocated and also tore the skin. It was the coolest thing I’ve ever seen, but it was disgusting, but like it, like it, it happens.

Perry: Right.

Perry: Um, you know, uh, Oh, man. How do you decide when, where you’re on the spectrum? Is it going to impact you and is it something that needs to be addressed? I’ll give you a great incident. My neck over the last two days have had a lot of discomforts. massive claw mark on one of the sides of someone like reaching out and just clawing me. And then I was doing front squats this morning and the barbell had knurling in the middle. So I don’t tell Aletha that she saw that when she said, what? She’s like, we’re going to Hawaii next week. You have a giant scratch on your neck. I’m like, don’t worry, it’s from Steve. She’s like, a guy scratched your neck. You should have seen the other guy. And I was doing front squats, and the knurling on the bar tore up my neck. And then I got home, my dog gave me a hug, and my dog scratched the other side of my neck. And clearly, that’s just discomfort. Things happen. Someone hits you in your funny bone or gives you a little Charlie horse.

Keith: I would say there’s definitely a hierarchy of trauma. Okay, I would say like traumatic brain injury Pretty high up there. Yeah, somebody’s been concussed and blacked out. That’s a brain injury.

Perry: Yeah, you know We have a student who doing one of our news noon students Joe and he had one years ago and And it’s fascinating working with him. He’s a great student. Dude, he’s, he’s strong, and he’s stable, and he feels great on the mats. But all the time, he’s like, man, I don’t have any balance. And I’m so weak. And it’s like, you might feel like you don’t have balance, and you might feel like you’re weak. Like that might be the sensation that you’re feeling. But let me tell you, my friend, imagine if you felt Yeah, connected.

Keith: Yeah, you know, and that and that’s, that’s where we’re getting at is the idea that okay, there’s been a traumatic brain injury. Has there been any type of auditory trauma? Has there been even long COVID with losing your sense of smell? Yeah, these are all neurons that project, how do you move in your environment to bring in that information in order to then execute what it is that you gotta do? How do I do this thing as effectively as possible without having to think about it? I just wanna do it, right? So I’d say there’s anything that deals with the face and the head, like eye trauma, jaw trauma, inner ear trauma, head trauma. Those are pretty, neck trauma, pretty high up there. Then I would put feet and hands.

Perry: I’m the worst and best coach. If it’s not your spine or your head and someone gets hurt, I’m like, you’re fine. I’m like, are you bleeding out? Is your spine okay? Is your head okay? Is your heart okay? Yeah, we’ll be good.

Keith: Right? Yeah. So if somebody has, if somebody has any type of genetic predisposition, those those are big, but like a nerve root problem. Yeah, somebody have a couple of nerve roots, like say, people call it like disc bulges. Yeah, somebody has some sort of bone growth in their spine, and it’s pushing against some nerves. that can be very challenging and take months to try to reorganize.

Perry: One of our old judo coaches, training partners, it’s actually Greg’s son, Dylan. He had a bunch of like nerve issues out in his arm, stemming from his shoulder and that like, it really bugged his arm.

Keith: Right. And that can also be from nerve root problems in the neck. So it all depends on, okay, where is the movement organization having problems with the tissues? So it’s really simply put, There’s, there are materials that you’re made out of, how you control them. And then how do you feel? So those three things stacked up is always my guiding principles to how I’m training. Like where, where do I have known problems? How did it feel? How did I control it? And I’m always looping back through those because again, if something happened to the spine, like if it’s an upper motor being eyes, ears, nose, all these things that are like higher centers of the brain, if that’s been traumatized, you’re not going to perceive your environment. You’re thinking it’s going to be one thing like your friend. But you’re feeling something else, and he’s not feeling that. So he’s like, I’m disconnected from what’s really happening, even though I feel this way. That’s very common.

Perry: I think it’s really important. I lift most mornings by myself, because Jeremy doesn’t get up early enough at 6 a.m. to come live with me.

Keith: Or he’s sick.

Perry: Or he’s sick. I’m just kidding. Get healthy, man. You’re great. But yeah, I usually lift up like 5.30 by myself in the mornings. Um, I, but Saturdays I, I live with you and it’s, it’s great to have someone that, uh, you know, even though the skillset that you have. 80% of the stuff that you catch on, you don’t need your skillset for. You know, you’d be like, hey, you see your left heels coming up when you’re doing a hack squat. It’s like, no, I didn’t notice that. But you know, thanks for telling me. But I think sometimes like people forget, sometimes your best training partner is just your phone. Like videotape yourself, a mirror’s great too.

Keith: But you know, it’s one of the, it’s even crazier in jiu-jitsu.

Perry: people don’t realize what their body is doing. And for me, especially when I do judo, and I have to do it when I do judo, because it’s so much, everything is quicker. Jiu-jitsu, I can do a jiu-jitsu technique pretty damn slow, at least most of them. Judo is like, you get to the point where you get in and you’re like, OK, now I need to throw the guy. You can’t really throw someone slowly. And it’s one of those things, like my coach Greg would always- It would look really weird. Yeah, I know. It’d be like, can you fly over me in slow motion? You’re falling. They’re going to fall at the speed of gravity or faster by the time they kind of get over that hump, right? But I’ve always struggled with my judo coach cueing me and me getting his cues. Like, hey, you’re missing this step. Or hey, your hip’s not getting in far enough. And what I would always have to do is, I’d be like, hey, can you just film me for a second? And then he would show me on film, I’d be like, ah, I see what you’re talking about now. And then I could fix it like, boom, right away.

Keith: I think what you’re really getting at is this idea of, this idea of the invitation to move. And there’s a specific, there are like a couple of different people out there calling it different things, like different styles of coaching. what somebody notices and asking questions about what they notice seems to be way more powerful than telling them how to do it. They call it an ecological approach to coaching, right? So I like to do that to myself while I’m training. It’s like the Socratic method.

Perry: It really is.

Keith: Question, question, question, question. Until they can deduce their own way to solve the problem, it’s not theirs. Yes, it’s only it’s only mine. So that if I if I want to make it sticky, I want to make that solution stick, right? They have to come up with with the solution, even though I’m like, I want to tell them like, Hey, this one is and this and this.

Perry: Yeah, this comes up in in kids classes all the time. We’re like, apparently like, well, why aren’t you correcting my kid and, you know, making them do it correctly? It’s like, because they’re not going to learn it that way. Like they need to, I will insert myself when I need to. But if they can self organize and figure that out on their own, right, it’s emerging, they will do it better and it will stick better, right? It’s like, you know, I could take your math homework and write down all the answers. But if I have you suffer through it a little bit, I kind of guide you along the way. I give you questions that are going to help you. you’ll learn it way better.

Keith: Chad GPT wrote that. You didn’t write it, Chad GPT did. So you’re telling me that this is now your essay. Like, no, it’s not your essay, right? So how do you go through the grind of finding solutions and help them with giving invitations for different ways to move? That’s why I love personally delivering my own constraints. So if I’m choosing better ways to learn, and this is exactly what I do with my exercise, anything for an adaptation, any skill, I’m going to take part of that and either play a game with it. That’s why the play is so important. Or I’m going to constrain it to a smaller, a smaller part of that whole skill.

Perry: Yeah.

Keith: So I’m like, I’m going to, instead of swinging the golf club, I’m going to jam something underneath my front arm. So now I can’t move this front arm, I have to move my torso. through. So now I have to get torso rotation. Yeah. And I can’t just use my arms, right? So what is the constraint to help learn the skill, and then take it back to the whole skill in a separate situation and scenario. So I’m a big fan of ecological coaching and whole part whole method. Yeah, by constraining the movements.

Perry: Yep. So yeah. Yeah, that’s a great point. I’m actually doing a how to coach jiu jitsu seminar tomorrow. And both of those are part of that.

Keith: Well, what was it? Great. What’s his first name?

Perry: Great.

Keith: Great. He wrote a book on ecological coaching.

Perry: Yeah.

Keith: And James Gibson. Yeah, it’s like the pioneer of that. Yeah, yeah. idea. It’s it’s fascinating. It’s a great tool in the toolbox, right? Right and plus empowering people with taking action Rewarding people by taking action and that’s why it’s like if you’re not starting To learn how to move. How are you gonna get better at moving?

Perry: I like giving people the example of when I learned how to handstand walk right, it’s It’s very simple, right? All I did was, hey, I want to go from here to the end of the room. And I’m just going to handstand walk. And as I keep going, every time I fall, my building my body brings up another little efficiency that I can work on. At some point in time, do I get fatigued and I can’t do it and I need to come back to it tomorrow? For sure, but your body will figure it out.

Keith: Right, right. And I love the idea of thinking, okay, here are these little pieces that I can do now. Your body wants to make things easy. Oh, completely. It wants to make things easy. It’s it’s looking for, again, how do I move in my environment? How do I conserve calories, right? And what what extrapolates this whole idea of training is like, number one, you can you can have a whole bunch of analgesics. Yeah, that help with pain, right. So when people normally come into us, they’re like, I have this pain, right? Tylenol, right? So there’s a whole bunch of ways for pain, right? You can get shots. Yeah, you have people that can cause it. You can you can do foam roll, you can do stick, you can do chiropractic, you can do stim, you can do all these things, right? None of them are looking at how you move to how you feel and quantifying and qualifying it. And then having, how does a person build the molecular machinery like muscle, tendon, ligament? It doesn’t happen without the stresses of force into the tendon. So unless you’re actually putting force into it, it’s not adapting and you are not solving the movement side of that problem of the pain movement problem. So it’s… it’s like yeah, there’s… there are other things that lead to pain that cannot be solved by exercise but you want to learn how to move. and you want to actually progress your movement, you better have a system in place to do it. And the system that everyone can do, we’re just gonna hand to you. And if you need extra help from things that you can’t observe by yourself and you want another coach to observe that to help make change happen faster, that’s what we do. You know, so it’s like there’s huge opportunities for everyone to just do it in their own home with even an ankle weight and maybe a band. Right, so it could be very low tech and if you have access to a place like social candy or yeah any gym Now you got some machines to quantify the load better cool, right? It’s all about what you how are you going to start and how are you going to be? Consistent so you can see those changes over the time because like seven to ten days is all it takes to change.

Perry: Well, one of my, one of my coaches, um, Chad Lyman, he, he oversees C4 CPJJ. So the association that we have to train police officers hit one of his sayings. I don’t know if it’s actually his or if he got from somewhere else, but it’s, it’s trained a little, a lot train. You just have to train a little bit, but frequency.

Keith: Well, I mean, think about return on investment. Exactly. It’s like, do you want to have a daily return of like 1% and know what happened throughout the entire year?

Perry: It’s that whole like, do you want a penny a day or a dollar a year or whatever it is, right?

Keith: It’s like the return is. massive if you just learn how to move, because what is being trained off of just moving your body, right? You’re building bone, you’re strengthening tendons, you’re helping ligaments, you’re training the powerhouses of the cell to become more efficient, you’re getting rid of waste products, right? So it’s just making you completely more efficient, and then you’re gonna sleep better. I mean, when you see people that age, that look like they age fast, either they’re doing a whole ton, or they’re doing nothing, right? There is a Goldilocks zone. And the only person that’s going to know the Goldilocks zone is you. So no one else can offload that. No one else can take that from you. They can only assist you. And the coaches that actually care are the ones that are like, do all these things. I want to power you to do these things.

Perry: Yeah.

Keith: And I’m going to help you change the least amount of time possible with complete honesty and transparency.

Perry: Yeah, nice. Oh, man. What else do you have to share? Anything else before we go into some, some big questions at the end? Big, maybe not serious question.

Keith: I mean, we’ll have our own podcast relaunching a little bit. If people are they want more information about different pathologies that maybe that that they have been through, expectations of healing, recovery, how to progress those things. We’re revamping our Biz Body podcast, which was originally just for gym owners and personal trainers and how to advance their own practice and help people. We’re shifting that more towards exercise practitioners and people that are enthusiasts that have a lot of experience that want to update all the latest on any types of trauma, how things heal, how to maybe do specific case studies on how to progress those things and what to look for, and then who to actually talk to, what type of health professionals to actually talk to. So that’s coming up very shortly.

Perry: And if people wanna work with you directly, based out of Mequon, Wisconsin, you got Body Activation.

Keith: Body Activation, LLC, that’s on Instagram, body-activation.com’s our website. Um, everything that we do is, um, we have free consults for anyone that, um, if you have an hour, I have an hour, we can talk about what you’re going through and how you want to progress. Uh, we work with people one-on-one hourly and half hourly. And, but then we also, um, do complete, um, app based training modules. And you have a gym. Yeah. And we have a gym. So we do in-house stuff. It’s it’s thirty five hundred square feet with all different types of machines, dumbbells, you name it. We we got different various.

Perry: And you help the whole spectrum, you know, whether it be a high school athlete to someone in their late ages to- We have 80 year olds- Major injuries to professional athletes.

Keith: Yeah, I mean, I have a person right now that can barely walk and we’re meeting with the neurologist because he’s actually making progress with something called transverse myelitis where normally people lose the ability to walk pretty rapidly. He’s been working his tail off in order to to stay walking. And we have one of our MLB guys who just went out early to camp. So it’s like we have professional athletes, high school athletes, and we have the people that they want to be able to walk for the rest of their lives. Nice.

Perry: So cool. Well, let’s wrap this up. We’ll do we’ll do three rapid fire questions each. Cool. I’ll start.

Perry: Stare down. If you could, if you could work with in your professional capacity, any professional athlete ever dead or alive, who would it be? Oh, geez.

Keith: Who would you want to help? You know, just because he was a childhood hero. Robin Yacht. Sweet. Yeah. Cool.

Perry: I mean, Robin, who doesn’t want some Robin? Yeah, yeah, yeah. What is your

Perry: What’s your favorite way?

Keith: Hold on a second. And if Robin Young, if you’re listening, I got to meet you someday because you’re the man.

Perry: Well, what is your favorite way to recover? My favorite? Oh, wow.

Keith: And it can be recover from from anything.

Perry: Like what’s your favorite like just way to.

Keith: I have a business partner that that works on me. OK. And when I get specific about that, I It’s amazing to have somebody actually find your weak spots because when all of a sudden you can control it, my HRV improves, my heart rate improves, my recovery improves. But like what I do for myself, it’s my nighttime routine. If I don’t play some guitar and I don’t do breathing, I feel like my night’s incomplete and I don’t rest well.

Perry: And then what’s your number one book you would recommend to the general public?

Keith: On anything.

Perry: John Cleese.

Keith: What’s that? Creativity. Simple, simple, small. I love, if you like Monty Python’s Flying Circus and Search for the Holy Grail, Life of Brian, that kind of stuff. One of the creators of Monty Python, It’s very simple, but… Yeah. And I would say that it’s something to really think about. Nice. All right, lay three on me. Three on you, okay.

Perry: Number one, what’s your protein number? What is my protein number? Like how many grams protein do I get a day? Yeah. I try to get one gram per body weight, so I try to hit 180.

Keith: So anyone knows about recovery, they’re gonna know these two numbers. Okay, what’s your water number?

Perry: How much water? 128 ounces. Instantaneous, right? But I wouldn’t count this of water. Yeah, OK.

Keith: So I’m a big fan of knowing those two numbers.

Perry: I also pee all of the time. The second I get off this podcast, I’m going to go pee. I’m going to fight you for the bathroom. An hour is hard.

Keith: Anyways. Lastly, OK. This is a two-parter. Boneless chicken wings or bone-in chicken wings? Boneless or bone-in chicken wings? Man, bone-in.

Perry: And now, buffalo or Jamaican jerk rub? Oh, dude, they’re both good. Like, if they’re both on the menu, I would probably get six and six. Yeah. It also really depends where it’s from. Ranch or blue cheese then? I like, I prefer ranch. Ranch, yeah. But I like buffalo, especially if they put the buffalo on, but then also grill the buffalo sauce. Oh yeah. Like I’m a big fan of any sauce on my wings getting like re-grilled and not just be slobbered on. That was a good one though.

Keith: So lastly, out of every machine that we’ve worked on together, is there a favorite?

Perry: Like every weightlifting machine? that’s really hard. That’s really hard. Can we put it to a body part? Okay, like your favorite leg machine favorite leg machine is probably the Man, I like a pendulum squat.

Keith: Pendulum squats are nice.

Perry: So I think it’s hard to get that pendulum squat feel without a pendulum squat. Right. Yeah. Smooth. Real smooth. I like it. And that could be the Panada or the Paramount. I think I like the Paramount because it’s older and it seems way more shady. I like the fact that it might actually, I feel like I like the fact that I might actually die using it.

Perry: It’s like a, it’s a big draw.

Perry: You may be crushed. Yeah, exactly. It’s a big draw to me using it.

Keith: What was the risk factor? What’s really cool is that I just got the Jammin.

Perry: Yeah, yeah, the squat.

Keith: Yeah, squat.

Perry: That one is also super shady looking. But guess what?

Keith: So I just picked it out and I found out that I realized now where I found, where I recognize it from. It was, we had one in our high school and I realized- You just used it decades ago? Dude, that was the one for my high school. He bought it from Sheboygan North High School. That’s crazy. So I was like, holy crap, this is the leg press that I had in school. That’s crazy. So I was like, okay, that’s too much. Cool.

Perry: That’s cool. We should probably hit that tomorrow. We should probably talk about working out after this. Yeah, for sure. Cool. All right, man. Well, I appreciate you coming on. Thanks for having me. I appreciate all of the work that you’ve done on me, all the workouts that we’ve done. And, you know, I hope anyone who’s out there injured, looking to get back on the mat, stay on the mats, increase performance, gives you a visit. And man, these things are amazing. Dude, elements so good. So good. So good. This is not an ad.